Authored by Jeffrey Tucker via The Epoch Times,

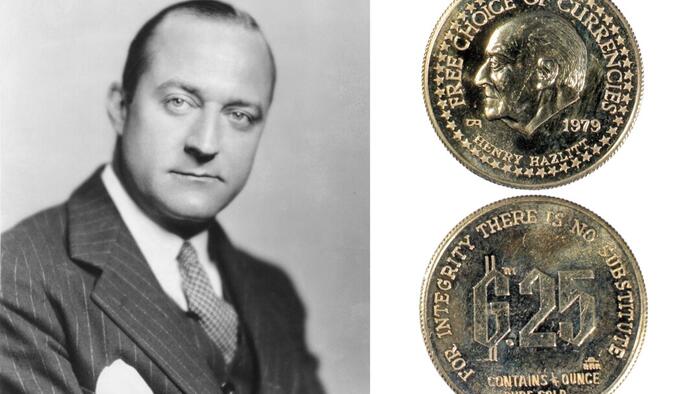

One of the most underrated intellectuals of the 20th century is Henry Hazlitt, author of “Economics in One Lesson” (1946). His career is far more varied than people know. Long before he was writing free-market treatises, he was a working journalist on Wall Street and, later, literary editor of The Nation and then H.L. Mencken’s chosen successor at The American Mercury.

His first published work is a wonderful little book published in 1922 called “The Way to Will Power.” He was only 28 when he wrote it, and spoke about the book none at all later. One suspects that he later found it too rudimentary or immature. Personally, I think it is wonderful.

The book aspires to apply what he learned as a financial reporter to matters of personal decision-making. His points are obvious once you think about them but, then as now, most people do not.

In finance and economics, the key to success is to match long-term ambitions with decisions one makes today. An orientation toward the future is always the key. He begins with the way a single price on the market today incorporates all knowns and expectations for the future. Silver might be $80 today not merely because of existing market conditions but based on the perception that there will be future uses, shortages, and high demand.

This is always a point about prices that confuses people. If there is a plan next year to permanently close a beach, the property values along the coastline will fall not next year but right now. This is because markets by their nature are always forward-looking. This is also why the price system always outwits the central planners. It benefits from its status as the composite wisdom of millions of buyers and sellers, whereas a government bureaucrat only knows what he knows.

Hazlitt wondered if there were ways to make our personal lives behave with as much intelligence.

He offers the example of the man who wants to lose weight, develop muscle tone, and upgrade his health. But night after night, he keeps choosing to go out gambling and drinking with his friends. Every morning he has a sense of regret about this and recommits to living a more healthy life.

Somehow his ambitions are not realized. He deeply desires health. The problem is that at no particular moment is health offered as an immediate alternative to drinking and staying out late. The choice on any particular evening is to go to bed early without fun or go have fun with his friends. He wants both health and fun but at every marginal unit of time, he always chooses fun over health and therefore never obtains his long-term goal.

In economics, this is the equivalent of a person who has high aspirations to build a large pool of personal savings from which he can earn interest, dividends, and increased financial valuations. But the consumption decisions he makes daily not only squander all the money he has but also drive him further into debt. He wants to be financially responsible but gains more personal advantage in the near term by doing what feels best at the moment.

To Hazlitt, the whole key to living a rich and rewarding life really comes down to this insight he gained from economics: match the decisions you make today with your dreams of how you want to live and who you want to be in the future. In other words, he urges not just a long-term orientation but a profound commitment today to making every decision about what it implies for the future.

Simple point? Maybe but it is easily overlooked, especially during the holidays.

We are surrounded by food and drink, invitations to indulge, and enjoy the freedom to sleep late and otherwise languish. The days are short and the weather is cold so the last thing on our minds is getting out, getting healthy, getting sober, and preparing for the future.

This is roughly where people are at the end of these days. And this is precisely why we have New Year’s resolutions. They reflect a sense of disgust over what the previous weeks have revealed about our own personal discipline and reflect a determination to change. Upon making the resolution—read more, get in shape, stop drinking—we are already feeling better as if adopting the ambition is half the battle.

The truth is that having a goal is none of the battle at all unless one’s decisions in the moment perfectly match one’s long-term hopes. Making resolutions stick means more than just imagining a better future. It means giving up right now that thing you want to do in order that the goal you desire is feasible and realized.

Hazlitt’s insight here is all the matching of time preferences. The here and now must embody the ambition of who you want to be in the future. This is particularly difficult when it comes to diet. A poor diet is addictive, and it is easy to swear it off following a huge meal over overindulgence. That’s the moment in which a fast seems like a great idea. That outlook lasts until the next morning when your empty stomach changes your mind.

What Hazlitt wrote here in 1922 contributed to the growing use of the term “willpower” in popular culture. We all just have to say no to the easy and quick thing in order to achieve that harder thing that unfolds over time. The example of the trade-off between consumption and investment is the best economic analogue: there can be no real prosperity for any society without the discipline to defer immediate consumption.

The sociologist Max Weber speculated that it was precisely the Protestant celebration of self-discipline and saving that bred the incredible prosperity of the West in the 19th century. The savings created a gigantic pool of capital for investment and empire building. The riches flowed and came to challenge the core values that gave rise to them in the first place. Frugality is forgotten when the money seems endless. Modest living and prudential management of material matters get sidelined.

In our own financial times, every major business and most smaller ones too have learned to live off leverage, as much as possible. If there is any chance an institution’s profit streams can outpace the cost of borrowing, living off debt can seem like the right thing to do. Of course this is only possible thanks to fiat money and the Federal Reserve system, without which the entire empire of debt would have collapsed long ago. In this way, our central banking institutions and profligate legislatures have undermined the whole basis of long-term prosperity.

There is a more insidious aspect to this pattern. When Hazlitt was writing in 1922, money was still gold and silver, interest rates were high and punishing, and hard work and savings were highly rewarded. There was a match between how government and finance lived and how we should live as individuals. In other words, the world made some sense.

It’s no longer clear that the functioning of finance and government makes much sense. If you and I lived in our private lives the way major corporations and legislatures function, we would live for the day, squander every dime, stay as inebriated as possible, and hope to foist the consequences of our misjudgements on others in the future.

Notice that Hazlitt’s view is all about having ambitions for the future rather than languishing in past trauma, as the culture says we should do today. This a fateful error. You can always use past trauma as an excuse for neglecting future triumphs.

Is it any wonder that the idea of willpower—which entered the vocabulary in the early 20th century—is so unfashionable? It just so happens that this very day, an attack on the notion appears in the nation’s major newspaper. The writer says we should forget about willpower (“overrated”) and adopt instead something she calls “situational agency.”

As best I can tell, she means that we should forget trying to resist temptation and instead structure our lives to eliminate it entirely. Perhaps this is the Ozempic theory of how to get thin. Forget saying no to pie and third helpings. Just take a pill to change your preferences entirely!

I have my doubts that pharmacology can overcome the core problem that Hazlitt identified. Indeed it seems like an excuse to pretend that the problem doesn’t exist at all. Surely there is some artificial means by which we can bypass the need for any self-discipline!

To restate Hazlitt’s core power, we all underestimate the power of the mind. Decide to quit smoking—really decide—and it is done. Same with drinking, overeating, and sloth in general. The difference between now and a better future is a simple change in thinking.

We will all make New Year’s resolutions, and most will be broken.

Once we reflect on why this is, we will be better positioned to match how we live today with the kind of life we want to have in the future. It’s the core human problem from time immemorial, one not easily swept away with fiat money, pills, and assurances that this time it will be different.

Loading recommendations…