Submitted by Thomas Kolbe

The fundamental problems of our society can largely be traced back to the collapse of reproduction rates. These are a symptom of dysfunction in the machinery of the social factory. People are losing faith in the future.

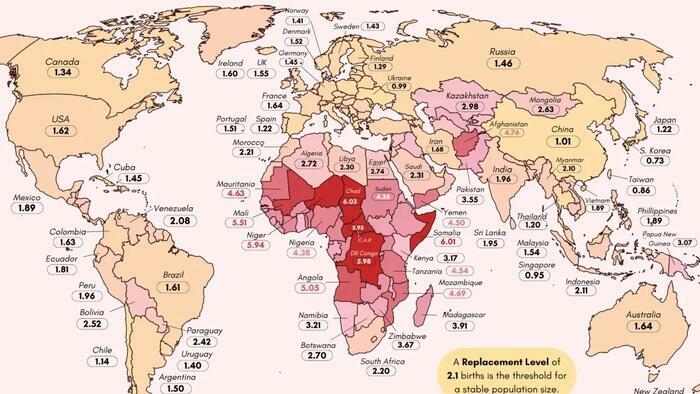

The dramatic decline in birth rates is no longer exclusively a Western phenomenon. China, long the epitome of demographic dynamism, has been in an open contraction process for about a year. The consequences are visible wherever political and social systems have been designed for steadily growing populations alongside rising economic productivity.

We know this problem from Germany. For the first time, the German society faces severe distribution conflicts and social struggles in its pay-as-you-go pension system as well as in healthcare provision for a rapidly aging population. The demographic foundation on which the welfare state was built is beginning to crumble. With its unprecedentedly naive immigration policy, the political class is operating like a dynamo, accelerating this development.

Much speculation surrounds the causes of this population decline. A valid point refers to the introduction of the contraceptive pill as a symbol of female emancipation – a medical-scientific intervention in reproduction rates that delivered a massive shock to 20th-century societies, still reverberating today.

The Eternal Reach into the Political Attic

To counter these trends, modern politics has devised a whole arsenal of monetary incentives: child allowances, tax incentives for marriage, joint taxation for couples, supplemented by a bouquet of state incentives. Yet all these measures have largely failed. Birth rates could not be sustainably stabilized, let alone increased.

A small anecdote illustrates how history repeats itself – at least in the sense that societies in demographic crises always fall back on the same reaction patterns. During the reign of Emperor Augustus, a decline in the Italian core population was met with a mix of monetary incentives for young parents and draconian tax penalties for childless members of the senatorial class. Both had little noticeable effect.

It is remarkable – and sobering – how persistently humans and political systems reproduce failed options, even when their failure is historically documented and empirically evident.

The Chinese example seems almost comical. During the population boom in the Middle Kingdom, a strict, heavily sanctioned one-child policy prevailed. Yet the population still grew – and with the now visible collapse of reproduction rates, Chinese leadership today follows the Western democratic model: offering child allowances while kindergartens visibly empty.

China is expected to lose about 20 percent of its population over the next 30 years.

There is no doubt this will have consequences for the global economy. Societies react reflexively to such developments. China responds with aggressive subsidies for its export engine to counter these domestic distortions, which primarily manifest economically as deflationary pressures.

Demographics, Intervention, and the Loss of the Generational Bond

Adjusting an economy to a shrinking population becomes increasingly difficult the higher the degree of political intervention. This is a central problem – not just for China, but also for Germany and Europe at large.

On a global scale, the population is expected to reach its peak in about ten years, around 9.7 billion. Currently, about 8.2 billion people live on the planet. Regions like China and Europe are already in a demographic downward spiral, while India and large parts of Africa continue to grow dynamically. This asynchrony exerts significant migration pressure on regions like Europe – leading to culturally consequential misjudgments, such as the EU’s planned relocation of millions of culturally foreign people to the continent.

Germany’s transformation into a kind of global welfare office has created a unique demographic situation. If open-border policies continue, the German population may even grow further in the coming years. Whether this is cause for celebration is debatable, given the state of German society.

But what has really happened here? The welfare state gradually transferred the responsibility for securing old age from the individual and their family to the institution itself. In the past, one’s old age was secured by children; today, the state assumes this role – financed by contributions from those still working. This increasingly dissolves the intergenerational bond between parents and children, both emotionally and economically – a kind of causal decoupling.

The emotional loss of family significance is difficult to overstate. The necessity for large families has disappeared.

The Fiat Money Shock

Examining demographic developments presents one of the most complex social structures imaginable. Remarkably, one central factor is consistently ignored: the monetary system under which these developments occur – the end of the gold standard.

By closing the so-called gold window in 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility into a fixed gold equivalent – marking the transition into the era of fiat credit money.

Money was no longer tied to real scarcity but could be politically manipulated through deficit policies and expanded through credit processes on an unprecedented scale. Credit became money; credit products like government bonds formed the foundation of the global monetary system.

This decoupling had far-reaching consequences. States effectively subordinated their central banks, using them to finance permanent deficits – a policy that, as we can observe in Germany today, eventually spirals out of control. It is an attempt to pull future purchasing power into the present, creating fiscal and economic leeway. A classic Keynesian maneuver that leaves nothing but debt, asset bubbles, and inflation.

The consequences of this nearly unbacked credit creation, especially in private banking, are visible in asset price development since the beginning of this era. Real estate shifted from consumer goods to financial instruments, quasi-piggy banks in the battle against systemic money devaluation.

Today, for young families, purchasing a home without plunging into massive debt is nearly impossible. Dual-income households have become a prerequisite. The focus on child-rearing has not only been socially devalued amid waves of feminism but is now also practically impossible for many economically.

In a credit-driven economy, life becomes a scarce resource. Two incomes are required to close the wealth gap with owners and heirs. Children inevitably compete with career, income, and private retirement planning.

It is a fatal dysfunction of the social factory, whose incentive structure should ideally produce at least enough children to stabilize the population.

A return to sound money could be the key to an economic and social turnaround, which also lies ahead for German society at the end of its decline.

It would simultaneously end the postmodern hyperstate, which, through credit manipulation, deeply interferes with individuals’ economic dispositions. With sound money and technological progress, people could gain purchasing power through disciplined saving – translated into time. Time they could devote to their families, projecting themselves into the future with confidence under stable monetary processes.

Loading recommendations…