Yves here. Since too many members of the US media exhibit the memory of goldfish, it’s important to keep tabs on Trump bluster and promises versus actual or predictable results. At the time of the Trump raid on Caracas, many pointed out it would take considerable time and investment merely to get Venezuela oil production back to the level of the 1990s, and vastly more to exceed that. This post provides more detail on the sorry state of Venezuela oil infrastructure and what that implies for increasing output.

By Matthew Smith, Oilprice.com’s Latin-America correspondent and an investment management professional. Originally published at OilPrice

- Venezuela’s oil industry collapse is rooted in decades of underinvestment, nationalization, sanctions, and infrastructure decay.

- Reviving production to historic levels could require $180 billion and more than a decade of sustained investment.

- Environmental damage, refinery failures, and a critical condensate shortage make rapid recovery highly unlikely.

After U.S. forces snatched Nicolas Maduro in a daring night raid earlier this month, President Donald Trump began pressing oil companies to invest in Venezuela’s heavily corroded petroleum industry. The U.S. president eagerly urged drillers to invest in Venezuela, which sits atop the world’s largest oil reserves, with Washington’s protection. But those overtures received a lukewarm reception from U.S. and European energy companies. ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods called Venezuela uninvestable provoking Trump’s ire, but some energy majors expressed favorable views, although commitments to invest were not forthcoming.

There was time when Venezuela, once a staunch U.S. ally and bulwark against communism in Latin America, was lifting over 3 million barrels of crude oil per day. Petroleum output hit a record high of 3,754,000 barrels per day in 1970. It was U.S. Big Oil investing billions of dollars to develop Venezuela’s massive oil reserves of over 300 billion barrels, which drove this impressive production growth. Even President Carlos Andrés Pérez’s 1976 nationalization of Venezuela’s hydrocarbon sector, which saw the newly formed national oil company PDVSA take control of industry operations, did little to deter foreign investment.

This did, however, mark a turning point for Venezuela’s oil industry. Production volumes diminished from that point onward, eventually hitting a multidecade low of just under 1.7 million barrels per day during 1985 as global oil prices plunged. Nonetheless, by the early 1990s output soared as U.S. and European energy companies boosted investment after Caracas eased regulations and offered highly profitable production contracts. As a result, production hit a multi-decade high of just under 3.5 million barrels per day during 1997, two years before Hugo Chavez became president and launched his socialist Bolivarian revolution.

Venezuela’s heavy sour crude oil was once highly popular with U.S. Gulf Coast refiners. A combination of Venezuela’s proximity to the Gulf Coast combined with a copious supply of heavy sour crude oil which sold at a significant discount to the Brent and West Texas Intermediate benchmarks made refining that petroleum lucrative. The only catch was refineries must be equipped with the additional technology required to distill and crack Venezuela’s heavy sour crude which is notoriously difficult to refine into high quality fuels. As a result, there was a flurry of construction activity throughout the 1970s and 1980s as refiners upgraded existing facilities or built new ones to handle Venezuela’s petroleum.

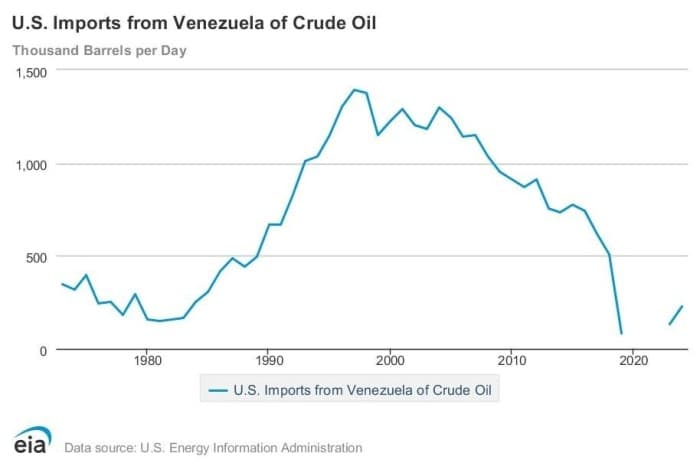

For those reasons, growing volumes of Venezuela’s heavy sour crude was shipped to the United States from the 1980s onwards.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Oil shipments eventually exceeded 1 million barrels per day by 1993, hitting an all-time high of just under 1.4 million barrels daily during 1997. The United States became a principal export market for Venezuela’s heavy sour crude oil blends and a major benefactor of the country’s massive oil boom. Oil cargoes received by the U.S. remained stable at over 1 million barrels per day throughout the early 2000s, until declining from 2006 onwards as Washington initiated sanctions and chronic malfeasance impacted PDVSA’s operations.

Hugo Chávez’s meteoric rise to power, which saw him assume Venezuela’s presidency in February 1999, marked the beginning of the end for the country’s economic backbone, its oil industry. The former army officer, who launched a failed coup in 1992, initiated his socialist Bolivarian revolution and took an increasingly hostile anti-imperialist stance against Washington and neoliberal economics. This culminated with Chavez nationalizing foreign privately controlled assets deemed vital to the economy, notably oil operations held by U.S. energy companies, costing drillers, like Exxon and ConocoPhillips billions of dollars.

By the mid-2000s, Venezuela’s oil output was once again in decline as U.S. sanctions, a lack of capital spending, and corroding infrastructure, along with a lack of skilled workers, sharply impacted operations. This accelerated as Washington ratcheted up sanctions, and oil prices collapsed toward the end of 2014. By the end of the 2020 pandemic, Venezuela’s energy infrastructure was in shambles. As a result, production plummeted to a historic low of 500,000 barrels per day during 2020. When coupled with ever stricter U.S. sanctions, oil cargos fell to negligible levels as decades of malfeasance, endemic corruption, and a lack of capital spending caused Venezuela’s oil industry to collapse.

While investment from China and Iran, including revamping decrepit oil infrastructure, along with Chevron being granted a U.S. Treasury license to lift oil in Venezuela, boosted production, it is well below levels witnessed during the 1970s and 1990s. Data from OPEC, of which Venezuela is a member, shows the near-failed state was pumping around one million barrels per day during 2025, less than a third of the mid-1990s peak. While Trump is aggressively pushing U.S. energy companies to invest in Venezuela’s heavily corroded oil industry, there is considerable speculation as to whether infrastructure can be rebuilt rapidly enough to materially boost production.

Professor Francisco Monaldi, director Latin American energy program at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, believes the damage is so severe that he estimates it requires annual spending of $10 billion over a decade before production recovers to historic levels. The professor says the White House must spend considerably more if it wishes to speed up Venezuela’s energy infrastructure recovery. Some analysts claim that more than $180 billion spent over at least 15 years must be invested to return Venezuela’s production to around 3 million barrels daily.

The parlous state of Venezuela’s oil infrastructure is indicated by the considerable environmental damage caused by corroded and degraded pipelines, storage facilities, well heads, derricks, and refineries. Scores of facilities in the heavy oil-producing Orinoco Belt, responsible for most of Venezuela’s petroleum production, have stood idle for a decade, seeing many cannibalized for spare parts by a near-bankrupt PDVSA or worse, looted by scavengers. That further increases the cost, complexity, and time required to bring production back online. Those events intensified as Venezuela’s economic collapse accelerated, forcing starving people to scavenge what they could to survive.

The disastrous collapse of Venezuela’s oil industry is underscored by the environmental catastrophe unfolding in and around Lake Maracaibo, the largest waterbody of its type in Latin America. Crude oil incessantly leaks from a sprawling network of corroded pipelines, storage tanks, and derricks which crisscross the waterbody. With over 10,000 petroleum-related installations dotted around Lake Maracaibo, the decaying pipelines, derricks, and storage tanks are extremely difficult to track, let alone repair or remove. The severe degradation of maintenance records and corporate memory within PDVSA means officials are unaware of the existing infrastructure in the area, further exacerbating this problem.

The corrosion from decades of neglect is further illustrated by the Amuay and Cardon refineries making up the Paraguana refinery complex in Falcon state. Both installations are believed to be operating at less than a fifth of capacity, which sees them increasingly used as de facto oil storage facilities. The Anuay and Cardon refineries also suffer from frequent mechanical failures, fires, explosions, and oil leaks, leading to long outages. Both are key to processing the extra-heavy ultra sour crude produced in Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt before it can be shipped and used as refinery feedstock. Estimates put refitting the Paraguana complex at $500 million to $1 billion, adding to the cost and complexity of revamping Venezuela’s oil industry.

There is a need to procure a reliable supply of condensate, a light hydrocarbon crucial for mixing with extra-heavy crude oil so that it flows, thereby allowing the petroleum to be processed and transported for use as refinery feedstock. This is next to impossible to secure in Venezuela, with the country’s light oil and condensate production ravaged by a lack of investment and heavily corroded drilling infrastructure. It is estimated that the OPEC member is pumping less than 20,000 barrels of condensate per day, making heavy oil production in the Orinoco Belt reliant upon importing the low-density, high API gravity hydrocarbon. Until recently, Iran was supplying naptha, a condensate derivative, to Caracas. Washington will need to procure a reliable supply of condensate if Venezuela’s crude oil production is to expand to the levels envisioned by the White House.