Yves here. The finding in the well-designed, multi-country study below is counterintuitive and very important. Sicker populations show less backing for more generous healthcare provisions than healthier ones. Is it because the extent of ill health raises the specter that a decent level of service translates into more society-wide costs? Or is it a particular manifestation of the general tendency that communities that perceive themselves to have some surplus are more receptive to funding social safety nets?

The authors also highlight the doom loop that seems to be starting in the US: that falling levels of well being translate into less support for broad-based medical programs, which then results in further declines in population-level fitness.

By Marcello Antonini, Visiting Fellow, Health Policy Department London School Of Economics And Political Science; Research Fellow, Centre for Primary Care and Health Services Research Department of Economics, University of Oxford and Joan Costa-i-Font, Professor of Health Economics London School Of Economics And Political Science. Originally published at VoxEU

People’s quality of life is directly affected by policy decisions about access to healthcare and funding, making it increasingly important to understand how the public interprets fairness. This column examines how people’s health status, proxied by exposure to the BCG vaccination, shapes their attitudes towards equal access to care and willingness to pay higher taxes. Individuals with better health are more supportive of fair health financing and equal access to care, suggesting that improving population health may bolster public backing for more equitable health systems.

Fairness in healthcare doesn’t simply mean giving everyone the same resources. In practice, what people view as ‘fair’ is shaped more by shared social norms and ideas of justice than by strict equality (Olsen 2011, Starmans et al. 2017). Most people accept some inequalities when they view the reasons behind them as legitimate, but reject those seen as arbitrary or unjust. Healthcare brings these fairness concerns into sharp focus because decisions about access and funding directly affect quality of life and, in many cases, survival. As health systems face rising costs, understanding how the public interprets fairness becomes increasingly important for policy design.

Healthy or Unhealthy Self-Interest?

A key unresolved question is how personal circumstances – especially one’s own health – shape attitudes toward fair access to care and fair financing of the health system. Evidence from COVID-19 reveals that exposure to the pandemic increased aversion to inequality, especially among those not directly affected by the pandemic (Costa-Font et al. 2021) and affected vaccination, a pro-social behaviour (Voth et al. 2021).

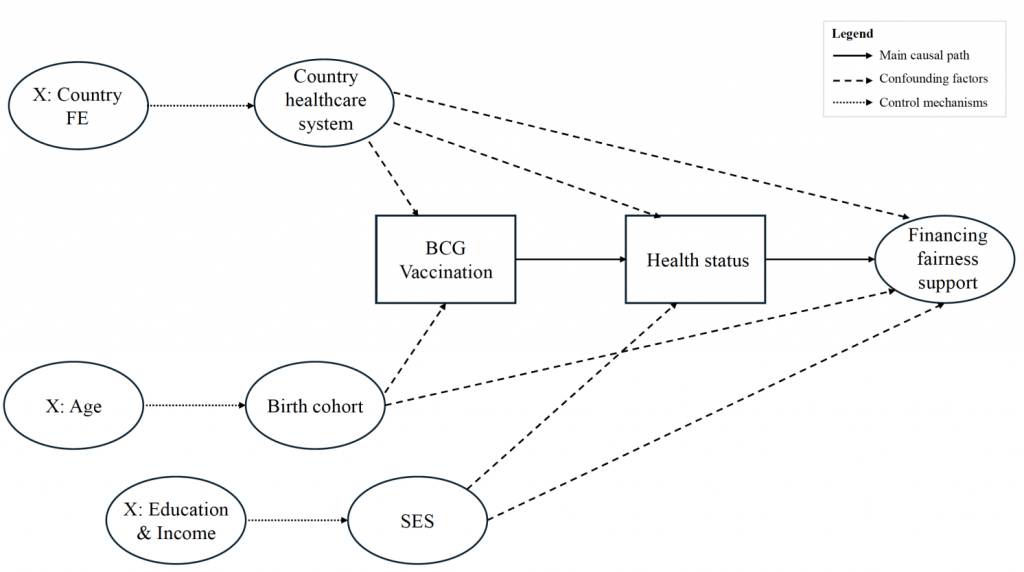

Figure 1 presents a directed acyclic graph that visualises our identification strategy, illustrating the causal pathway from BCG vaccination to health status to preferences for financing fairness, as well as potential confounding factors that our methodology addresses. We consider two competing hypotheses:

- The ‘healthy self-interest’ hypothesis suggests that people in poor health support redistributive policies because they benefit more directly from them, while healthier individuals may prefer approaches based on personal responsibility.

- The ‘unhealthy self-interest’ hypothesis proposes the opposite: that people in poor health narrow their focus to immediate personal needs and therefore show less concern for system-wide fairness, whereas healthier individuals may have more capacity to support fairness norms.

Figure 1 Directed acyclic graph of BCG vaccination instrumental-variable strategy

Health and Attitudes to Health System Fairness

To test for the effect of health-on-health system fairness, in Antonini and Costa-Font (2025) we examine evidence from more than 70,000 respondents in 22 countries, linking self-reported health with attitudes toward equal access and willingness to pay higher taxes for better public healthcare.

Figure 2 illustrates a positive association between exposure to the BCG vaccination and both dimensions of financing fairness preferences. This positive association is particularly pronounced for attitudes toward fair access, which also show higher average scores compared to willingness to support fair financing.

Figure 2 Association between exposure to BCG vaccination and (1) attitudes toward fair access and (2) willingness to support fair financing, at the country level

Notes: The figure depicts a scatter plot of the instrument (exposure to BCG vaccination) against the two outcomes of the analysis: attitudes toward fair access (panel 1) and willingness to support fair financing (panel 2), at the country level. The size of the circles reflects the standard deviation of the two outcome variables measured in each country. To create this scatter plot, we first calculated the average concerns for both outcomes for each country. Subsequently, we plot the mean values of the concern variables on the y-axis and the share of the population exposed to BCG vaccination on the x-axis.

The graphical inspection suggests that our instrument may be a valid candidate for the analysis. Our causal estimates are retrieved from a novel instrumental-variable strategy based on variation in BCG vaccination exposure, allowing us to estimate the causal effect of health status on fairness preferences. This approach helps address the long-standing challenge of separating the influence of health from other social or economic factors.

The results clearly support the ‘unhealthy self-interest’ hypothesis. Individuals in worse health were less supportive of fair health financing, while healthier individuals showed stronger support for both equal access and more redistributive funding. A one-point improvement in self-reported health increased support for fair access by 11% and support for fair financing by 8%. These findings suggest that improving population health may not only enhance wellbeing but also bolster public backing for more equitable health systems.

Our findings suggest a stronger effect on normative judgements compared to behavioural intentions involving personal costs, suggesting that health status has a more pronounced impact when no personal financial sacrifice is required. This pattern indicates that while healthier individuals express greater support for fairness principles, this support somewhat diminishes when it involves actual financial contribution.

The mechanisms driving these effects operate primarily through economic pathways (income and employment), with healthcare trust and political attitudes playing contributing roles. This helps explain why healthier individuals, who typically have better economic outcomes, demonstrate greater preferences for fairness in healthcare financing.

These findings also help explain why more unequal societies often experience poorer health outcomes such as lower life expectancy, higher obesity rates, greater substance abuse, and worse mental health. When people experience ill-health, their support for fairness in healthcare access and financing weakens, making it less likely that policies aimed at improving equity will gain traction. Notably, this pattern appears across very different healthcare systems, suggesting that the link between personal health and support for financing fairness is universal, even if its strength varies by institutional context.

The causal connection between better health and stronger support for fair healthcare financing points to a potential virtuous cycle. As health systems succeed in improving population health, public backing for equitable policies may naturally increase. This dynamic may help explain why health inequalities sometimes follow a Kuznets-type curve (Costa-Font et al. 2018). It also reinforces the case for investing in health improvements as a foundation for long-term equity. As overall health rises, systems may be better positioned to apply fairness-oriented allocation tools – such as fairness weights – and to prioritise historically overlooked groups whose needs become more visible.

See original post for references