We have been warning of China being in the grips of deflation. If it becomes entrenched, which is a realistic risk, the downside is considerable. Deflation leads to business closures, falling incomes and job losses. Those effects can then kick off a deflationary spiral. Bad economic conditions and falling prices lead businesses to hunker down and defer spending, which then intensifies the contraction. On top of that, falling prices increase the cost of debt in real terms. That produces defaults, which reduce investor incomes and can lead to bank failures, or at least to a great reduction in new lending, again amplifying the depression.

China is particularly exposed due to its lack of demographic growth and further decline in births, and its high private debt to GDP levels. Some sources put that on the par with the US, which is particularly striking given that China is a less developed and supposedly less financialized economy. Some believe that actual private debt to GDP levels are even worse. Recall that it is excessive private debt to GDP levels that generate financial crises.

We’ll turn to new evidence that the situation is getting worse, not better, despite China reporting 5% GDP growth for the last quarter. Aside from the fact that there is long-standing skepticism about China’s official growth figures, the growth that China has been having had been in its exports. It has not been sufficiently widely noted that the increased dependence on exports is a shift.

Even though China had been stereotyped as export driven (it has yet to transition to a consumer-led economy), it had for many years had investment, particularly in real estate, as a bigger driver of growth. The Economist last week took note of the shift:

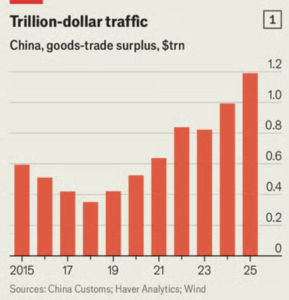

In a chaotic world, China did the predictable thing. Its economy met the official growth target for 2025, according to figures released on January 19th, just as it had the year before and the year before that. GDP grew by 5%, although China’s population fell even faster than forecast. Growth was boosted by a record trade surplus, which reached almost $1.2trn, despite the country’s tariff war with America (see chart 1).

The unexpected strength of China’s exports last year made up for the weakness of other sources of spending. The government had set itself the task of “vigorously boosting consumption”, but households did not play along. They saved an even higher share of their income in 2025 (32%) than they had the year before (31.7%)…..

China has usually relied on investment spending to keep its economy humming. But according to the official figures, fixed-asset investment (FAI) shrank in 2025 for the first time since 1989 (see chart 2). The slump in property investment continued, accompanied by a decline in infrastructure spending and negligible growth (0.6%) in manufacturing investment. The combined figure is so awful that many economists refuse to take it at face value.

Another official measure of investment—gross capital formation—suggests that capital spending continued to expand, albeit slowly, last year. Investment accounted for 0.75 percentage points of China’s overall growth, a seventh of the total, according to Mr Kang [Yi, head of the National Bureau of Statistics]. For that to be true, investment must have increased by about 2% in real terms.

Some of the glaring gap between the two statistics may reflect technical differences. FAI is not adjusted for inflation, excludes inventories and includes land purchases. But it is also possible that China’s local governments are now understating the growth of fai to make up for overstatements in the past.

China’s trade surplus is so large that it is already pushing the limits of what its partners can absorb. China is already deporting deflation to Southeast Asia. Europe is facing poor growth prospects, so its ability to absorb much more in the way of exports from China is questionable. Trump trashing the dollar will have the effect of reducing US demand, even with US dependence on China in many sectors.

We’ll turn soon to a new Wall Street Journal article which gives a solid recap of recent data plus some local color. Additional sightings:

🇨🇳 China struggles with the longest deflation period in decades!

Chart: @Bloomberg pic.twitter.com/yq7gROMf0u

— Alex Joosten (@joosteninvestor) January 27, 2026

Chinese consumer spending is now falling. Never happened before outside of lockdowns. This isn’t a month or two, the contraction is seven months and counting. Stimulus didn’t work. Instead, Chinese consumers are – like Americans – very worried about jobs and incomes.

All the… pic.twitter.com/zSOucFh4ac

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_EDU) January 21, 2026

And from the South China Morning Post at the beginning of January, China must take action to avoid Japan-style deflation spiral, scholars warn:

As China grapples with persistent deflationary pressure, scholars from one of the country’s top universities have urged the government to take more forceful action to prevent the economy from becoming trapped in a Japan-style downward spiral…

“Japan’s experience has shown that once households form the expectation that prices won’t rise over the medium to long term, it becomes nearly impossible to break that mindset,” said He Xiaobei, a professor at Peking University’s National School of Development.

“Japan has only just emerged from deflation – but that was largely driven by external shocks like the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war,” she said, stressing that it was not caused by changing public expectations…

Prices in China have remained largely flat for years, with the country’s consumer price index growing at less than 1 per cent for 33 months in a row and factory-gate prices stuck in a prolonged contraction that has lasted more than three years.

China’s gross domestic product deflator – a key indicator that tracks the price changes of all goods and services – has been falling for 10 consecutive quarters, the longest downturn recorded since data first became available in the 1990s, according to the Peking University report.

Falling prices can trigger a vicious cycle as wages are dragged down and then households become less willing to consume, adding further deflationary pressure, He said. The longer low prices persist, the harder it becomes to escape the downward spiral, she added.

Now to the Journal story. We will skip over its discussion of “involution” which is the government’s attempt to underplay its deflation problem by rebranding it. China has acknowledged, with “involution,” that it has what US economists in the 19th century called “ruinous competition,” the result of overinvestment and resulting overcapacity, in key sectors such as electric vehicles and solar panels. China had an earlier overcapacity/deflationary pressures problem in middle of the last decade, which it did combat successfully. Most experts argue that it will be harder to do this time due to the difficultly of rationalizing these sectors (for instance, electronic vehicle plants often had investment support of local governments; rationalizing would mean making some areas winners and others losers) along with the sheer magnitude of the challenge being greater this time/

The Deflation Doom Loop Trapping China’s Economy starts with an extended anecdote about how vendors at China’s biggest wholesale clothes market are handling more returns than sales, since retailers can send back unsold wares. From the article proper:

Across China’s economy, consumers aren’t spending enough and producers are making too much. That leaves companies all along the supply chain earning less. Many feel they have no choice but to lower prices to unload inventory, eating into profits.

With less money on hand, businesses are limiting wage growth, pausing hiring and shedding employees, which means workers have less to spend, continuing the vicious cycle….

Corporate filings show profits shrinking at companies in a wide range of industries, including steel, concrete, electric vehicles, robotics, condiments and cosmetics. Profit margins among publicly traded companies in China are at their lowest levels since 2009, according to a FactSet index of 5,000 mainland-domiciled firms.

Fixed-asset investment—which tracks spending on assets such as homes, factories and roads—fell in 2025 for the first time on record.

The risk is that China could get stuck in a prolonged period of stagnation similar to what Japan experienced during the 1990s and early 2000s—a mindset that becomes ingrained over time and even harder to shift.

Deflation is increasingly a geopolitical liability. Squeezed in China, manufacturers are exporting more, notching a record $1.2 trillion trade surplus in 2025. Governments around the world are complaining about an influx of cheap Chinese goods that could hurt local industries.…

When Beijing sets economic goals, provinces and municipalities compete for glory. Local governments pour money into industries, creating a flood of companies all fighting to come out on top.

The system has made local governments and the financial system more incentivized to boost production than consumer spending. Businesses get cheap loans from Chinese banks, as well as investments and tax breaks from local governments.

Meanwhile, many everyday Chinese get by with bare-bones health insurance or small pensions, sometimes as low as around $30 a month. While the government has worked to strengthen the social safety net over the years, China’s spending on such programs still lags behind many large economies.

As a result, people tend to save for emergencies rather than spend. The average Chinese household stashes about one-third of its income, while Americans save less than 5%. Household spending made up only 40% of China’s gross domestic product in 2024, compared with a world average of around 55%—and a U.S. average of about 68%, according to the World Bank…..

The multiyear property-market slump—another example of overcapacity in China—is weighing further on spending.

It also describes that overcapacity extends beyond the oft-cited electric vehicle and solar panel sectors:

The humanoid robotics sector—one of Beijing’s newer favored industries—may already be falling into the pattern of overinvestment and excess competition. China’s top economic-planning agency last year warned of the risk of a bubble, with more than 150 companies in the industry.

Nontech sectors are also struggling. China’s paper industry was supported by significant government subsidies in the 2000s and has continued to suffer from overcapacity on and off for years. In the first 11 months of 2025, profits among large paper makers fell about 11% year over year, according to government data.

Shandong Chenming Paper, one of China’s biggest paper manufacturers, cut prices. Its profits shrank, then turned into mounting losses. As of June, it had racked up more than $500 million in overdue debt, had hundreds of bank accounts frozen and was forced to shut down production lines, according to a filing.

Rising pet ownership in China has sparked a rush of companies into making items such as dog food, leashes and toys. Eric Yan, a manager at Petstar, a pet product maker in Hangzhou, said the industry has become extremely competitive, with new rivals cutting prices and constantly rolling out new designs.

Honworld Group, the holding company for cooking wine and soy sauce maker Lao Heng He in Zhejiang province, said household spending was weaker than expected, leading other brands to unload inventory at low prices…

After more examples, the Journal describes a classic deflationary symptom, falling wages and employment:

With businesses struggling to make money, employees are having to do more work for less while companies avoid making new hires. Wage growth has stalled. Surveys by the People’s Bank of China show widespread anxiety about job prospects. The unemployment rate among 16- to 24-year-olds, excluding students, was around 17% in November, according to government data.

The article omits a key reason why China may not be able to free itself from this trap. President Xi is deeply committed to China’s having technological and manufacturing primacy and is philosophically opposed to much in the way of social safety nets. From a 2023 post:

However, as we have pointed out (following Michael Pettis and Marshall Auerback, among others) and PlutoniumKun highlights, China seems not just to be having what would be expected difficulty in changing from an investment/export led growth model to one with domestic consumption being far more important. China also appears to have an ideological, or one might say political problem in making this shift. Higher consumption would require lower savings rates. Not only do Chinese consumers not feel secure enough to do that (too much history of crises in China and its neighbors) but China under Xi is unwilling to implement the social safety nets that would encourage more spending.

I don’t want to take up too much time with this intro, but some relevant recent sightings. Note that Setser among other things is the man on dollar holdings and flows outside the US:

I suspected that parts of China’s top leadership objected to a household focused stimulus. Turns out the epicenter of opposition is Xi himself: “Xi sees such growth as wasteful and at odds with his goal of making China a world-leading industrial and technological powerhouse”

2/

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) August 27, 2023

Beijing’s mind seems made up — but Chinese policy makers have this backwards.

Using the central government’s clean balance sheet to support household demand would actually make it easier for households, property developers and local governments to delever.

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) August 27, 2023

A hypothesis: there can be no durably stable Chinese and global economy so long China’s national savings rate stays around 45% of GDP …

(note that, contrary to the IMF’s forecasts, savings has been rising since 2020 …)

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) August 28, 2023

China’s shoppers hesitate to spend big in face of deflation via @FT

🇨🇳

”Excess savings in China have increased in the first half of the year compared with the same period last year, and there is still a gap between pre-pandemic and current consumption” https://t.co/dvQvhP1lrU

— Iikka Korhonen (@IikkaKorhonen) August 29, 2023

Even though many have predicted that China’s growth model would hit its sell-by date many year ago, and China has defied those expectations, as economist Herbert Stein said, “That which can’t continue, won’t.” China looks finally to have hit that limit.