Yet more evidence that improving the lot of those at the very bottom of the income ladder does not necessarily produce unemployment or runaway inflation.

Just under a month ago, Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum announced that the country’s minimum daily salary would increase 13% in 2026, from 278 pesos to 315 pesos. In the northern border regions, where wages are higher, the increase would be 5%, taking the minimum daily wage to 440 pesos.

The wage hike, which will reportedly benefit 8.5 million Mexican workers, was part of an agreement between labour, business and government leaders, Labour Minister Marath Bolanos said.

A New Year’s Tradition

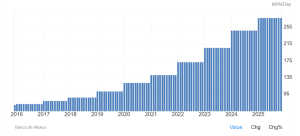

Double-digit minimum salary increases have become a New Year tradition in Mexico in recent times. Since 2018, the minimum daily salary has almost quadrupled in nominal terms, from the miserly 88 pesos (just under $5) granted by the former Enrique Peña Nieto government to today’s 315 pesos ($17.50).

As you can see in the graphic below, courtesy of Trading Economics, there have been seven steep increases in the minimum wage since December 2018, not counting the one that just went into effect.

Accounting for official inflation, the latest minimum wage increase will bring the accumulated rise in salaries to 154% in eight years. Yet when the former leftist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador began this process, many opposition politicians, business leaders and economists warned that it would fuel inflation as well as risk higher unemployment.

Neither of these things have come to pass. Today, official unemployment in Mexico is 2.7%, close to its lowest level on record. That is despite the impact of US President Donald Trump’s on-again, off-again tariffs and the acute uncertainty over the upcoming review of the United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) trade deal.

As you can see in the graph below, courtesy of Trading Economics, unemployment has actually been trending at lower levels over the past three years than it did before AMLO’s election in 2018.

In other words, Mexico’s eight year experiment with minimum wage increases has had a significant net positive effect on the incomes of millions of Mexican workers, helping to lift an estimated 13.4 million people out of poverty, without lowering their unemployment prospects.

Meanwhile, inflation in Mexico has waxed and waned since 2018, reaching a peak of 8.7% in 2022. However, that peak was largely fuelled by the pent-up demand and global supply chain pressures triggered by the opening up of the world’s COVID-19 locked down economies, and subsided relatively quickly. In fact, Mexico’s peak was somewhat lower than those of other OECD economies, including the US (9.1%), the UK (11.1%) and Spain (10.8%).

Mexico’s Consumer Price Index is now at 3.8%, which is one percentage point lower than the level it was at in late 2018, when the minimum daily wage was roughly 70% lower than it is today.

As Luis F Munguía, the president of Mexico’s National Minimum Wage Commission, writes in an interesting article for Phenomenal World, one of the main reasons why inflation hasn’t surged as a result of the sharp minimum wage hikes is that the minimum wage was so low to begin with.

In May, 2016, CNN’s Spanish did a study comparing the minimum statutory wage of over a dozen Latin American countries set against each country’s performance on the Big Mac index, with the US Dollar as the benchmark currency. Mexico, the region’s second largest economy, came in 13th out of 13, behind a host of much smaller, weaker economies, including El Salvador and Guatemala.

In Mexico, the legal minimum wage at that time was 74 pesos, or around $4 per day. That was the equivalent of $0.50 per hour, compared to $1.40 in Brazil, $1.45 in Peru, $2.07 in Ecuador and Chile, $2.38 in Argentina (soon to increase by 33%) and $2.43 in Uruguay.

A minimum-wage worker had to clock in 5.6 hours to be able to get his or her lips around a Big Mac — over triple the number of hours a Salvadorian had to work to receive the same “reward.” In other words, Latin America’s second largest economy had a significantly lower minimum-wage purchasing power than its tiny neighbour to the south.

As I noted in an article for WOLF STREET at the time, the Big Mac index, while hardly a perfect measuring stick, is still one of the best measures of a currency’s comparative value currently available:

It was invented by The Economist in 1986 as a lighthearted guide to whether currencies are at their “correct” level, but since then it has become a global standard, included in several economic textbooks and the subject of at least 20 academic studies. As The Economist itself recently conceded, a better measure of the current fair value of a currency would be the relationship between Big Mac prices and GDP per person, on the basis of which the authors calculated that the Mexican peso was undervalued by 43%.

Reversing a 70% Loss in Purchasing Power

So, how did Mexico, one of Latin America’s two super-size economies, end up having one of the region’s lowest minimum salaries?

Through a heady mixture of economic crises (the hyperinflation of the late ’70s, the so-called lost decade of the 1980s, and the Tequila Crisis of 1994), corporate profiteering and trade liberalisation, recounts Munguía (emphasis my own):

In 1976, after nearly three decades of gradual growth, the minimum wage reached an all-time high of $20.76 per day (in 2025 equivalent terms).3 The following year, however, the country faced an economic crisis marked by hyperinflation and massive unemployment. The authorities responded by freezing wage adjustments below the inflationary pace, which, together with the indexation of other wages to the minimum, led to a 75 percent loss of purchasing power in the following decades.

After the crisis and into the 1990s, Mexico adopted an economic model based on neoliberal policies centered on trade liberalization, global integration, and building deeper ties within North America. To compete internationally, the government opted to keep wages artificially low, freezing the daily minimum wage at around $5.25 (adjusted to current prices) between 1990 and 2017. This stagnation was only broken with a meager 4 percent real increase toward the end of the period, mainly a result of accumulated social pressures that led the minimum wage to be decoupled from various legal provisions.

The turning point came in 2018, during the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Faced with growing citizen demand for wage improvements, a team of economists from the progressive-oriented Colegio de México evaluated the feasibility of increasing the minimum wage without destabilizing the economy. Aiming to reconcile social justice with macroeconomic stability, a gradual and technically sustainable recovery strategy was implemented that restored the lost purchasing power within seven years.

Interestingly, notes Munguía, the first stage of this process began in 2016, during the PRI-controlled government of Enrique Peña Nieto, when constitutional reforms for the “de-indexation of the minimum wage” were approved:

This step was taken in consideration of warnings from the business sector and some voices from the labor sphere, who both argued that increasing the minimum wage was unfeasible due to the risk of triggering an inflationary spiral. This claim had some truth to it, since in Mexico many essential components of the economy were linked to the minimum wage. Fines in most cities were expressed in terms of minimum wages; certain private loans and those corresponding to the Instituto del Fondo Nacional de la Vivienda para los Trabajadores (Infonavit) were similarly indexed to the minimum wage. Many collective bargaining agreements provided for wage increases and benefits calculated in terms of the minimum wage.

Consequently, it was essential to decouple these standards. In 2014, after facing immense public pressure, the government of Mexico City presented the first document which highlighted the need to both increase and de-index the minimum wage. A year later, various leftist legislators, led by the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), formally proposed the de-indexation, with representatives of the labor sector of Conasami supporting the initiative. Finally, in 2016, the minimum wage was separated from these indexes, paving the way for subsequent increases. However, in 2017, despite the announcement of a “historic” increase, the minimum wage barely registered increases of 3.2 percent and 4.7 percent in real terms.

The first double-digit increase came in late December of 2018 with a 16.9% rise for the entire country except for the Northern Border Free Zone (Zona Libre de la Frontera Norte, ZLFN)— which comprises the forty-three municipalities that border the United States and all municipalities in the state of Baja California — where the minimum wage doubled.

The doubling of the minimum wage in the north was meant as a controlled trial before proceeding with the long-term plan at the national level, notes Munguía. Needless to say, the hike was fiercely opposed by the business sector which warned it could fuel inflationary pressures. To mitigate that risk, the government created a package of tax incentives for the northern border region, including reductions in Income Tax (ISR) and Value Added Tax (VAT):

[T]o the surprise of many, the initial inflation data obtained in the north showed lower prices. Inflation continued to be substantially lower that year in the north than in the rest of the country. This finding definitively dispelled the myth that increasing the minimum wage always leads to inflation.

Since then, the Mexican government has implemented seven further double-digit increases to the national minimum wage. With the 2024 hike, Mexico’s minimum wage was finally brought to a level higher than those in half of Latin America, notes Munguía. The increases are also considered instrumental in lifting 6.64 million people out of poverty between 2016-24 — roughly half the total number (13.4 million people).

However, each rise in the minimum wage continues to face stiff opposition from large segments of the business sector, despite the fact that higher basic salaries tend to translate into stronger internal demand and consumption:

In the first years of the minimum wage policy, the business sector only repeated the argument that increasing minimum wage would cause inflation. But as data continued to show low inflation, or even lower inflation, in areas with higher minimum wages, their argument lost credibility. Similarly, evidence showing that the Mexican labor market is monopsonistic and that the minimum wage has zero effect on employment disproved the sector’s argument around decreased employment.

With each hike in the wage, the business sector resisted, as higher wages came at the consequence of higher labor costs (although business indirectly benefited from increased consumption). But thanks to a plethora of research, the business sector has been convinced on numerous occasions of the advantages of strengthening the domestic market through higher income for workers.

Unions, in turn, were “timid and cautious” at the beginning of the wage increases, relaying concerns similar to those of the business sector. Somewhat ironically, unions expressed greater fears than the companies themselves, despite international cases demonstrating positive effects for workers. Over time, however, unions became more “combative,” even presenting proposals from various unions requesting increases above the established estimates.

Next Target: a 40-Hour Week

Mexico’s success with minimum wage hikes should not come as a surprise — at least not outside the hallowed halls of Ivy League economics faculties. As Yves has mentioned before, classic studies by David Card and Alan Krueger on the impact of minimum wage increases on the income and employment levels of fast food workers showed that increasing minimum wages does not in fact produce unemployment.

Germany’s recent experience implementing a minimum wage has shown similar findings. Many economists and segments of the media warned that it would trigger up to 900,000 job losses, none of which has happened.

Back in Mexico, the AMLO government’s sharp increases in the minimum wage between 2018 and 2024 played a key role in Claudia Sheinbaum’s landslide victory in 2024. Who would have thought that improving the lot of the poorest in society would translate into electoral success?

For its part, the Sheinbaum government has proposed a new piece of landmark labour reform that awaits approval in 2026: the piecemeal establishment of a 40-hour working week by trimming two years off the current 48-hour week each year between 2027 and 2030. As with the minimum wage hikes, the proposed reform will affect millions of Mexican workers.

Mexico is the OECD country with the longest working hours, reaching 2207 hours per year in 2023. Of the 13.4 million people who work more than 40 hours per week, 8.6 million are on the job for 41-48 hours, while 2.76 million put in 49-57 hours, according to data from the national statistics agency INEGI (and relayed by Mexico News Daily). Another two million work more than 58 hours.

The proposed reforms also seek to establish limits on the numbers of hours workers can be asked to put in per day (12; a regular eight-hour shift plus a maximum of four hours of overtime) as well as the number of days workers can be asked to work overtime hours (four). It also proposes that overtime hours must be paid at double the agreed rate for normal hours and prohibits overtime hours for workers aged under 18.

Meanwhile, Colombia’s outgoing Gustavo Petro government, which Trump has threatened to topple, is poised to implement a 22.7% hike to the country’s minimum wage. And guess what? International media outlets like Reuters are warning of a subsequent sharp rise in inflation and unemployment. Some things, I guess, will never change.