Yves here. I am of two minds in even now calling attention to the before-year-end action in the Fed’s repo facility. We’ve had repeated instances, most notably in the 2019 repo panic, of commentators getting whipped up over a nothingburger. This was another one.

Several readers e-mailed us, citing wild-eyed accounts from supposed experts over late-December spikes in repo facility usage, depicting them as representing stealth bank bailouts. We have the receipts via e-mailed responses at the time that this reaction was way overblown. We did not even want to dignify this line of thinking at the time by amplifying it through a refutation (cognitive bias research shows that trying to debunk is actually very hard to do effectively; it more often has the effect of reinforcing the message one is trying to counter).

Wolf presents the data. He points out, as we did, that year end is typically a time of low liquidity. Many institutional investors try to close their books as of December 15.

In addition, the Fed has changed the way it manages short-term liquidity which, as far as I can tell (expert opinion welcomed) has seemed to make matters worse in crunch times. After the crisis, it went from managing short-term liquidity mainly via daily open market operations to paying interest on reserves, which is a completely unwarranted gimmie to banks. That approach operationally works fine in loose monetary conditions but not in a tightening cycle. 3 months before the 2019 repo panic, the New York Fed “lost” the two top traders on its money desk, which leads me to think they were told the role of the unit was being curtailed. My perception, based on subsequent events, is that the Fed has been and still is inept in using the repo facility as an alternative to money desk interventions. There may also have been a loss of market intelligence by downgrading the role of the once-very-important New York Fed money desk.

In addition, around this year end, the CME raise margin requirements sharply for some metals. It is not hard to think some banks hoarded liquidity in case hedgies who were wrong-footed by the move in turn pulled down hard on their borrowing lines to meet margin calls.

We had pinged derivatives maven Satyajit Das for his reading at the time. From his reply:

1. Money market conditions are choppy primarily because of year-end and also the Treasury’s reliance on T-bills for funding. There is also deep uncertainty around the Fed and interest rates. I am aware that bank funding costs have increased for these reasons. An additional factor is the concern around credit ‘cockroaches’ (to use JP Morgan CEO Dimon’s expression) lurking in the system which may result in larger credit losses than provided for. There are concerns around exposure to hedge funds and commodity business due to rises in margin calls due to higher price volatility.

2. I am aware that the fed has stepped up its repo operations to ‘smooth’ short term fluctuations which is a normal part of its remit. The amounts mentioned in the article or not that large in the overall scheme.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

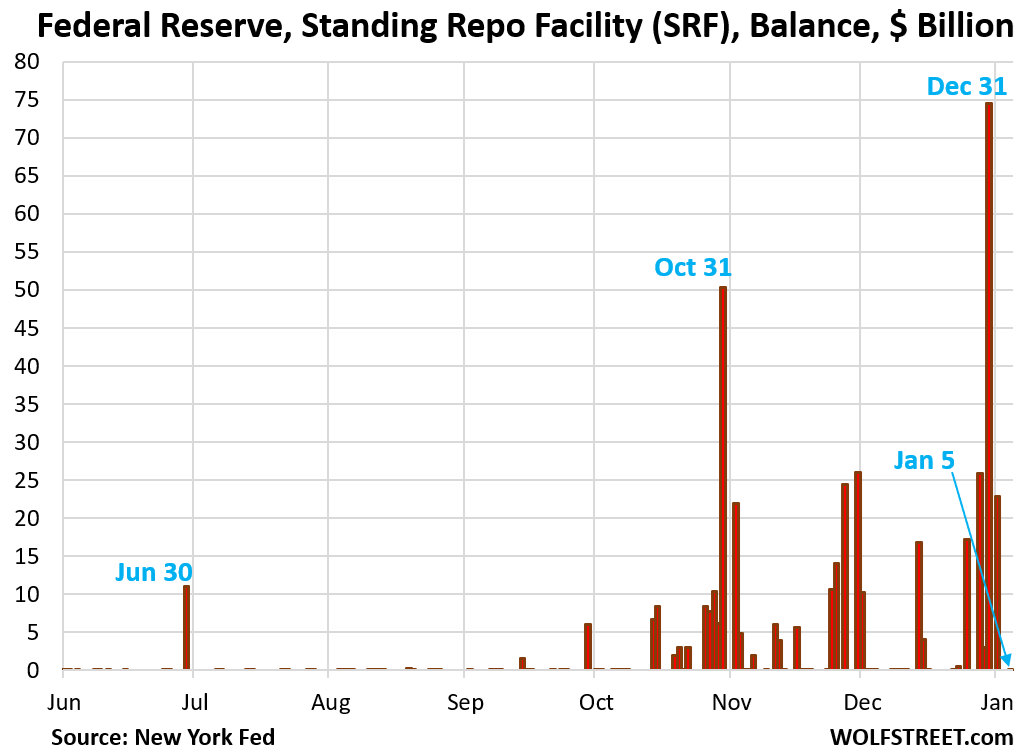

The balance at the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF), an asset on the Fed’s balance sheet, fell back to zero today, with all repos from Friday unwinding, and zero new repos being taken up at the two auctions today, as expected.

The SRF had spiked to $75 billion on December 31 as part of the year-end liquidity shifts, from zero before Christmas, and that $75 billion had been the largest factor in the $104 billion spike of the Fed’s weekly balance sheet as of the close of business on Wednesday, December 31.

But this spike has now completely reversed; and the Fed’s next weekly balance sheet, to be released on Thursday, will show a substantial drop in total assets.

At year-end, massive amounts of liquidity shifted around markets, causing tight spots in some places, as reflected in the spike of repo market rates, such as SOFR, and excesses in other places, as reflected in the spike at the Fed’s overnight reverse repos (ON RRPs) which drain liquidity from the markets.

The tight spots showed up in repo market rates, such as those tracked by SOFR, which surged at the end of December, with some transaction rates as high as 4.0% on December 31. On that day, SOFR – a calculated median for the day’s rates – jumped to 3.87%.

This spike in repo rates made it profitable for banks to borrow $75 billion at the SRF on December 31 at 3.75% and lend to the repo market at higher rates through the holiday until Friday morning.

On Friday, January 2, as repo market rates dropped – the high was down to 3.87%, and SOFR was down to 3.75% – that profit opportunity vanished, and banks unwound most of their repos at the SRF on Friday, and unwound the rest today, and the balance went back to zero today.

But the Fed’s weekly balance sheet, which shows balances as of the close of business on Wednesday, had booked that $75 billion one-day-wonder spike at the SRF that had occurred on Wednesday, and that had been the primary factor in the $104 billion spike of the Fed’s total assets on its balance sheet released on Friday.

But the Fed got its $75 billion back, and the counterparties got their collateral back, and that $75 billion has now been completely unwound and vanished from the Fed’s assets.

The excess liquidity that had occurred in other parts of the market on December 31 showed up at the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility (ON RRPs). And it has been unwound nearly entirely.

That excess was reflected in the spike to $106 billion at the Fed’s ON RRP facility on Wednesday, December 31.

ON RRPs mostly reflect excess cash that money market funds have put on deposit at the Fed; they in essence lend their excess cash to the Fed and earn 3.5% on it. The Fed owes them this cash, and so ON RRPs are a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet.

On Friday January 2, the ON RRP balance plunged to $6 billion, from $106 billion on December 31. Today it remained at $6 billion. So this too has settled down, as expected.

These two facilities at the Fed – the SRF and ON RRPs – are part of the Fed’s system of control of short-term interest rates to keep them in the range of its monetary policy rates, currently 3.5% to 3.75%.

The SRF rate acts as a ceiling rate – one of the tools to keep overnight rates from surging too far above the Fed’s top end of the range (3.75%).

The ON RRP rate acts as a floor rate – one of the tools to keep short-term rates from dropping too far below the Fed’s bottom end of the range (3.5%).

And the counterparties of these two facilities are not the same, and so the rates affect different parts of the market: The counterparties of the SRF are 43 big banks, broker-dealers, and a credit union (I posted the updated list in the comments below). The counterparties of the ON RRPs are mostly money market funds.

After three years of QT removed $2.43 trillion in liquidity from the markets, these kinds of brief liquidity shifts are going to show up on key dates during the year, such as year-end, quarter-end, month-end, and particularly on Tax Days, such as around April 15.