Alert readers immediately noticed the disconnect between Trump’s signature braggadocio and the more cautious remarks from the other members of Trump’s team after the kidnapping of Venezuela’s president Nicholas Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores. Trump skipped the narco-terrorism pretext despite a US indictment being the pretext for the abduction; he instead talked up having US companies exploit Venezuela’s reserves: “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country.”

But many observers quickly compared the Trump press conference to Bush’s “Mission Accomplished” moment as the Venezuela government not only remains in place but its acting president Delcy Rodriguez maintains that Maduro remains the country’s leader and that Venezuela will not cede to US colonialist demands. And perhaps being a smidge more realistic, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, by contrast, presented the US as having narrower aims, of simply removing Maduro, at the initial presser, and has been trying to square the circle of Trump being high on his show of force versus the fact that the US is not even remotely in control of Venezuela. From Politico:

In the wake of the U.S.’s capture of Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro, Secretary of State Marco Rubio on Sunday made it clear that it is somewhat unclear what’s next for the Latin American country.

His comments come as Democratic leaders continue to decry the administration’s actions in Venezuela and push for the White House to seek congressional approval for such military operations.

In multiple interviews, Rubio emphasized that the U.S. is not at war with Venezuela but stopped short of explaining exactly what the U.S. role in the country will look like as both nations reel from Maduro’s arrest — and in the aftermath of President Donald Trump’s statement Saturday that the U.S. would “run” Venezuela for an indeterminate time.

“We are at war against drug trafficking organizations, not at war against Venezuela,” Rubio told NBC’s “Meet the Press.” Rubio added that oil sanctions will remain in place, and the U.S. reserves the right to issue strikes against alleged drug boats heading toward America.

But while Rubio told CBS’ “Face the Nation” that the U.S. is not occupying Venezuela, he did not reject the idea that it could be a future option from the Trump administration.

Trump, Rubio said, “does not feel like he is going to publicly rule out options that are available for the United States, even though that’s not what you’re seeing right now.”

“What you’re seeing right now is a quarantine that allows us to exert tremendous leverage over what happens next,” he added.

Many experts with knowledge of the region, such as Larry Johnson, have given repeated, long-form accounts of how much harder it would be to conquer Venezuela that Iraq, even before factoring in that our army is much smaller and weaker now than then. A short version of this line of argument from Modern War Monitor:

Venezuela is heavily armed. Years of political polarization, along with an expanded role for security forces and pro-government colectivos, mean that weapons and combat experience are not in short supply. The country’s borders are long, porous and already used by guerrillas, paramilitaries, and criminal networks.

To see what that might look like in practice, you don’t have to speculate; you can look next door. Colombia’s armed conflict, officially dating from 1964, pitted the state against FARC, ELN, and a web of paramilitary and criminal actors for decades. It persisted, in part, because armed groups could slip across borders, find safe havens, move contraband, and restock. Even with massive US funding under Plan Colombia and repeated “final” offensives, the state never achieved a clean victory; violence simply changed shape.

Translate that pattern into a post-Maduro Venezuela run in practice by US–backed figures, and you can sketch the basic dynamic. There will be bombings of police stations and government offices, high-profile assassinations, and attacks on oil infrastructure. Kidnapping Americans or US contractors will become a lucrative tactic. Armed groups will drift across the Colombian and Brazilian borders and into the jungle or mountains when pressure grows.

Even Sky News is reporting that men and women on the street are speaking out on behalf of the current regime:

🗣️ “The US is not interested in freedom or democracy, it is interested in our oil.”

Venezuelans gathered in Caracas to express their solidarity with Nicolas Maduro, who was captured by the United States following a series of airstrikes.

Latest updates: https://t.co/4w875fZU8W pic.twitter.com/b5byRmj15m

— Sky News (@SkyNews) January 4, 2026

So oil theater is signature Trump, of acting like empty bags have value. He talked up his “raw earths” deal with Zelensky, which still proved to be a difficult negotiation even with the US theoretically holding all the card by providing Ukraine with critical intel and targeting along with weapons, particularly air defenses. And that’s before getting to the fact that as of when the agreement was inked, over one-half of the “Ukraine” reserves were in Russian hands, and how much of Ukraine eventually winds up being formally part of Russia and/or in a rump Ukraine that is a Russian vassal is up in the air. Similarly, in the 28 to 20 point piece plan floating about, Trump’s negotiators Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner claim that one of two really key US demands involves joint ownership of the Zaporzhizhia nuclear power plant and the disposition of its energy. This idea is delusional. Russia deems Zaprozhizhia to be part of Russia and is not going to hand part of the nuclear facility to the US to make nice to Trump.

We’ve already discussed that wringing more production out of Venezuela’s oil fields would require a long period of investment before any real payoff took place. And the precedent of Iraq, where we had occupied the country, bodes ill. Despite oil being seen as the most logical objective for the US invasion, it was years before oil producers started investing.

Admittedly, the embargo is increasing pressure on the Venezuela government.

Venezuela’s state oil company PDVSA is cutting crude production because it is running out of storage capacity due to an ongoing US oil blockade that has halted exports, increasing pressure on the interim government https://t.co/eAelegFxHM pic.twitter.com/sIs9UqaQei

— Reuters Business (@ReutersBiz) January 5, 2026

So why not stick with Plan A? Was this yet another manifestation of Trump’s extreme need to be seen as dominating world events? To create a distraction from the Epstein files and increasing certainty that Russia will secure a military victory in Ukraine, which will mean Trump lost? IMHO the initial apparent success of the Trump “Raid not invade” in Caracas almost assures that he will take Greenland when Ukraine is clearly toast.

Not surprisingly, the mainstream media is raising eyebrows over Trump’s grandiose oil exploitation claims. It is true that the US has motive, in that our refineries are tuned so that 70% of the oil they process is heavier grades, despite the US producing light sweet crudes.1 And commentators have pointed out that after the US sanctioned Russia, cutting it off from its medium heavy crude. Even though Russian supplies purportedly represented only 3% of US imports and experts predicted that its loss would matter little to the US, Biden turned to Venezuela almost immediately after imposing the shock and awe sanctions, explicitly to replace Russian fuel.

However, heavy and sour (as in sulfur-ridden) crude of the Venezuela sort is expensive to process. The current low oil price environment, driven by less-than-robust growth in much of the world,2 is an unfavorable backdrop, even before getting to perfectly reasonable big corporate concerns about safety and expropriation risk. Do not be fooled by Trump likely succeeding in having a flurry of meetings with big oil execs. There was also a lot of dog-and-pony showing for a Ukraine reconstruction fund, starting under Biden, that continued with Trump. Many misread the involvement of giant fund manager BlackRock, which had signed up only as an adviser and had not committed any money.

We featured an OilPrice article in late 2025 that argued that it didn’t make economic sense for the US to try to seize Venezuela’s oil. First from our long intro:

This article explains why Venezuela’s oil is not of much strategic value to the US and its infrastructure would take a lot of investment over a long time to bring up to snuff. Yet Trump has shifted his justification from narco-terrorism to, erm, retaking the oil and other assets, in going to war with Venezuela (recall a blockade is an act of war)…

Recall that after the weapons of mass destruction justification for the Iraq war fell apart, the Administration then provided a series of pretexts, even as most observers argued that the oil was the reason. Iraq then had the world’s second largest proven reserves, and they were highly prized light sweet crude. And while the US still has substantial control over Iraq’s oil exports, the US were slow to invest in Iraq’s oil infrastructure. I cannot find the source, but I recall reading that the majors were not comfortable the US level of exploitation of the Iraqi resource….

A 2012 Aljazeera story intimated that the Western firms, even though they won the critical oil concessions after the war, had not done as well as they had hoped, confirming the idea that the exploitation of the Iraq resource was not handled in an expeditious manner….

But my impression is that the later theories, that Iraq was a stepping stone on the way to subjugating Iran, and the oil was at most a secondary objective, are on target.

From the OilPrice article proper:

- Despite accusations from Venezuelan and Colombian leaders, the immense growth in U.S. domestic oil production and reserves significantly diminishes the strategic need for Washington to seize Venezuela’s oil fields.

- The U.S. Gulf Coast refining industry has largely transitioned away from Venezuelan heavy crude due to facility closures and a shift toward alternative suppliers like Canada, Mexico, and domestic shale sources.

- Restoring Venezuela’s dilapidated oil infrastructure to major export levels would require over a decade of work and tens of billions in investment, making a military seizure economically impractical for the United States.

The Wall Street Journal story flagged in our headline comes to similar conclusions. From Trump Wants to Unlock Venezuela’s Oil Reserves. A Huge Challenge Awaits:

The Trump administration’s move to oust Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro…. will pave the way for U.S. oil companies to regain a foothold in the South American nation, President Trump said at a Mar-a-Lago press conference.

“We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure, and start making money for the country,” he said.

But getting foreign companies to flock back to Venezuela will be a massive challenge. Chevron is the only major U.S. oil company there…. Other oil executives will be forced to gauge the stability on the ground in a country where the industry has fallen into disarray…

The other obstacle facing Trump’s effort to put more of Venezuela’s viscous crude into the global market is that the world doesn’t have much of an appetite for more oil…

The U.S. hasn’t detailed the mechanics of how it would bring more American oil companies into Venezuela to boost production. Analysts say it could facilitate a process that would allow companies to bid for oil and gas blocks and question whether European companies could also bid for the right to enter the country.

As readers know, that assumes subjugation of Venezuela or cooperation that has yet to be in evidence. The article cited a statement by Chevron being “focused” on employee safety and “integrity” of its Venezuela operation. Not hard to read that as an expression of heightened concern. In passing, it also signaled doubt about whether the level of Venezuelan reserves are as large as claimed (supposedly the largest in the world). This is not crazy. Matthew Simmons of Peak Oil fame produced tables showing OPEC members posting sudden increases in claimed reserves, which he documented had no substantiation (as in no new discoveries or changes in production methods that could lead to bigger supplies from existing assets). He argued a big reason for these rises was that OPEC set production levels among its members based on their proven reserves.

Back to the Journal:

In the U.S., the shale boom unleashed record levels of oil production, but the kind of oil American frackers are pumping doesn’t work as well as heavy crude produced in Venezuela, Canada and Mexico. Venezuela’s government says its proved oil reserves top 300 billion barrels, which, if true, would make its bounty the world’s largest.

Other big oil companies that are potentially interested in re-entering Venezuela will almost certainly take time to evaluate the situation because the country has a track record of appropriating oil assets, as it did in the 1970s and the 2000s, analysts said.

ConocoPhillips and Exxon Mobil pulled out of Venezuela in 2007 after then-President Hugo Chávez nationalized their assets. Conoco later sued the Venezuelan government for more than $20 billion; Exxon sued for $12 billion. The companies were awarded fractions of their losses in protracted arbitration proceedings…

Orlando Ochoa, a Caracas-based economist and a visiting fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, described the Herculean task of jump-starting the moribund energy industry, which has seen tens of thousands of trained professionals flee the country under Maduro’s authoritarian rule.

He said that includes drafting a broad economic stabilization plan to attract the financing Venezuela badly needs from multilateral lenders to rebuild infrastructure and rusted oil-field installations. Local laws need to be modified to allow private energy firms to operate without state overreach, he added. And the government has to restructure some $160 billion in debt and settle pending arbitration cases with foreign companies to convince them to come back.

“What the U.S. needs to do is to implement a form of a Marshall Plan,” said Ochoa, referring to the economic program that helped rebuild Europe after World War II. “This is about much more than coming into the oil and gas sector just to extract crude from the ground.”

Good luck with that. This is from a bunch that is so seat-of-the-pants that it can’t even conduct negotiations with Russia on a disciplined basis.

Reuters echoes the Journal’s concerns:

Venezuela was a founding member of OPEC with Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Its struggles with electricity production have repeatedly hampered mining and oil operations.

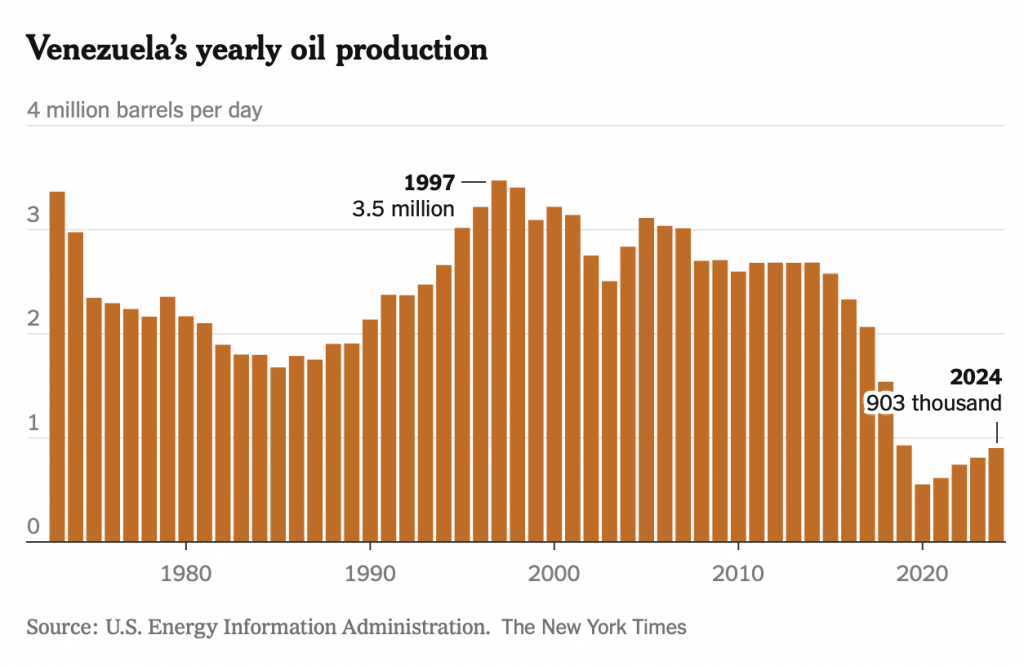

The country was producing as much as 3.5 million barrels per day of crude in the 1970s, which at the time represented over 7% of global oil output. Production fell below 2 million bpd during the 2010s and averaged some 1.1 million bpd last year or just 1% of global production. That’s roughly the same production as the U.S. state of North Dakota.

“If developments ultimately lead to a genuine regime change, this could even result in more oil on the market over time. However, it will take time for production to recover fully,” said Arne Lohmann Rasmussen from Global Risk Management…

“History shows that forced regime change rarely stabilises oil supply quickly, with Libya and Iraq offering clear and sobering precedents,” said Jorge Leon, head of geopolitical analysis at Rystad Energy.

Reuters usefully presents 2019 and 2021 data from Venezuela on gold, coal and nickel reserves. It also includes this interesting factoid:

Venezuela owes about $10 billion to China after China became the largest lender under late President Hugo Chavez.

Venezuela repays loans with crude transported in three very large crude carriers previously co-owned by Venezuela and China.

But Reuters oddly does not mention the large gas field off the coast of Venezuela and Guyana, which relates to a long-standing territorial dispute.3

Finally from the New York Times:

The national oil company, known as PDVSA, lacks the capital and expertise to increase production. The country’s oil fields are run down and suffer from “years of insufficient drilling, dilapidated infrastructure, frequent power cuts and equipment theft,” according to a recent study by Energy Aspects, a research firm. The United States has placed sanctions on Venezuelan oil, which is now exported primarily to China…..

In theory, if U.S. oil companies were given greater access in Venezuela, they could help gradually turn the industry around. “But it’s not going to be a straightforward proposition,” said Richard Bronze, head of geopolitics at Energy Aspects.

Analysts say increasing Venezuelan production will not be cheap. Energy Aspects estimated that adding another half a million barrels a day of production would cost $10 billion and take about two years.

Major increases might require “tens of billions of dollars over multiple years,” the firm said.

Some experts are throwing even more cold water on the Trump hoped-for oil heist. Be sure to click through. The analysis is detailed and devastating.

I have spent a lot of time talking shit at people with opinions on Venezuela’s oil production potential, and how it’s going to “RePLaCe CanADa”. So here’s my contribution — how I see the cost of replacing Canadian crude with Venezuelan heavy.

I think it’s a nearly $1 trillion… pic.twitter.com/XFlPVwPdew

— Michael Spyker (@ShaleTier7) January 4, 2026

To entice you to read the whole tweet, one paragraph from the middle:

The problem is they don’t have the power infrastructure to add the power needed for 3MMBbls/d of SAGD for steam generation, and even for primary recovery they don’t have the electricity they need. So you need to build 10-15 GW of new power infra, at gas-fired capital cost including transmission and the new midstream infra to move gas (including LNG import terminals), that’s another $40-75Bn just to get the power to the SAGD facilities. There are constant rolling blackouts in the country. You also need ~7-900MB/d of diluent looping on the Venezuela side, including DRUs for another ~$25Bn. Other local midstream refurb is at least $15Bn to replace ashphalted and corroded trunk lines. Any North American firm would also have to commit to cleaning up Lake Maracaibo which is a $10Bn commitment.

So this Trump romp in South America is sure to end badly. The big open question is whether Trump decides to break more china there or goes TACO and moves to other, seemingly easier, targets.

____

1 Thanks to the state of search, I have been unable to find estimates of how much it would cost to retune a refinery to process lighter grades, although I infer that ne>wer refineries make this possible at lower cost than for older ones. Per the American Fuel & Petroleum Manufacturers website :

Long before the U.S. shale boom, when global production of light sweet crude oil was declining, we made significant investments in our refineries to process heavier, high-sulfur crude oils that were more widely available in the global market. These investments were made to ensure U.S. refineries would have access to the feedstocks needed to produce gasoline, diesel and jet fuel. Heavier crude is now an essential feedstock for many U.S. refineries. Substituting it for U.S. light sweet crude oil would make these facilities less efficient and competitive, leading to a decline in fuel production and higher costs for consumers.

2 Trump tariffs and Chinese overinvestment and resulting deflation are big drivers. Neither looks set to change soon.

3 Among other things, Venezuela has credibly alleged that the long-ago arbitrator was bribed. I am skipping over this topic for now, but those interested, please see The Guyana-Venezuela dispute and UK involvement and Guyana’s Oil Wealth Drives Tensions With Venezuela. So one view is that the subjugation of Venezuela would also solve the Venezuela dispute with Guyana and facilitate development there.