Boom Supersonic, the company trying to bring back faster-than-sound commercial flight, just closed a $300 million funding round by pivoting into an unlikely business: selling turbines to power AI data centers.

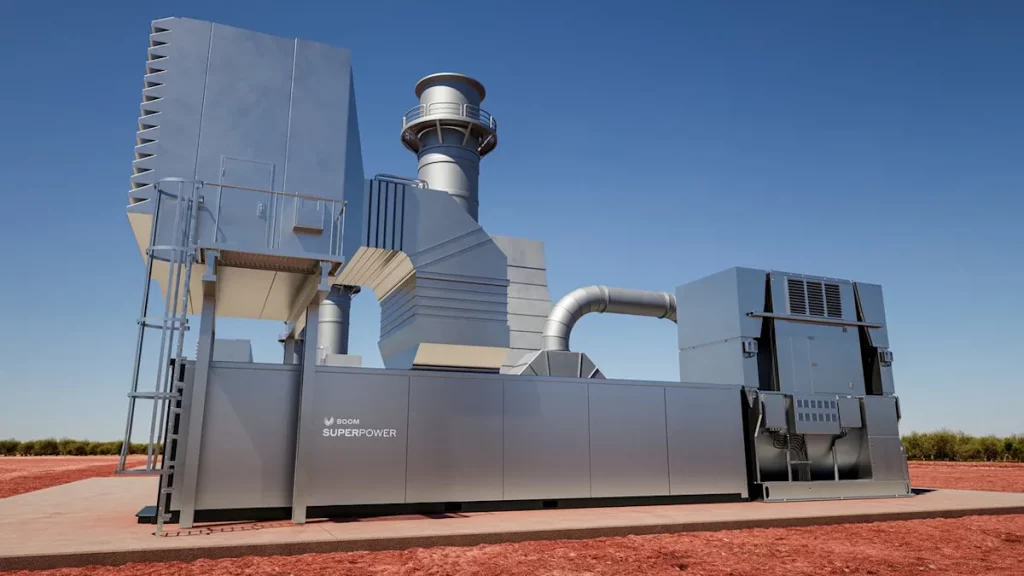

The Denver-based startup announced Tuesday that it secured Crusoe, a data center developer, as its first customer for a new product called Superpower. Crusoe ordered 29 turbines capable of generating 1.21 gigawatts of power, with Boom claiming it has a backlog of more than $1.25 billion in orders for the technology.

The deal emerged from what CEO Blake Scholl described as scrolling on X, where he kept seeing posts about power shortages hitting AI data centers. After texting OpenAI CEO Sam Altman to confirm the crisis was real, Scholl discovered his engineering team had already sketched out plans to adapt the company’s Symphony supersonic engine into a stationary power turbine.

The pivot makes technical sense. Supersonic engines run continuously at extreme thermal loads, exactly what data centers need for reliable power generation. Each 42-megawatt Superpower turbine operates on natural gas without requiring a water supply, addressing two of the biggest constraints facing data center expansion.

But Boom is entering a market with severe supply constraints, and it’s unclear whether the company has solved them or will hit the same walls. Major turbine manufacturers, like GE Vernova and Siemens Energy, are currently quoting wait times of five to seven years for new orders. The delays stem from pandemic-era supply chain damage that hasn’t recovered, material shortages affecting all power plant components, and limited global manufacturing capacity.

Boom says it’s building a “Superpower Superfactory” and has already started manufacturing its first turbine, with plans to scale production to more than 4 gigawatts annually by 2030. The company says it went from concept to signed deal in about three months. But Boom hasn’t explained how it will avoid the supply chain bottlenecks and material shortages plaguing manufacturers with decades of turbine experience and established factories. The company also hasn’t said when Crusoe will actually receive its 29 turbines or whether customers ordering today will wait years like everyone else.

For Boom, the timing solves a critical funding problem. The company successfully flew its XB-1 demonstrator past the sound barrier in January, validating key technologies for its planned Overture airliner. But scaling up to commercial production requires enormous capital. The turbine business offers a faster path to revenue while the company works toward test flights of Overture in 2027 and hoped-for commercial service by 2030.

The deal also reflects how desperate the AI industry has become for power. Tech companies are projected to spend roughly $400 billion on AI infrastructure this year, with much of that going toward data centers. Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft have collectively taken on more than $121 billion in new debt over the past year to finance construction, a more than 300 percent increase from typical levels.

Some of those financing arrangements are raising concerns about aggressive accounting practices. Meta recently structured a $27 billion data center deal using a special purpose vehicle that keeps the debt off its balance sheet, prompting comparisons to Enron-era accounting tricks. Other circular investment deals between Nvidia, OpenAI, and data center operators have analysts warning about bubble dynamics reminiscent of the dot-com era.