Yves here. Forgive us for being a bit heavy today on AI-related posts, but a bit of a breather on Trump whipsaws allows us to catch up on some important topics. This one confirms concerns about the way that AI is being used more and more to replace original creative works and is harming what passes for culture in the West.

Note that this development is taking place along side a more general erosion of cultural values, as a result of younger adults not reading books much if at all as well as the teaching of the classics being degraded due to being largely the output of white men. But studying humanities has also been under assault for at least two decades due to being perceived as unhelpful to productivity. For instance, from Time Magazine after Larry Summers was forced out as Harvard President:

And humanities professors had long simmered about Summers perceived prejudice against the softer sciences — he had reportedly told a former humanities dean that economists were known to be smarter than sociologists, so they should be paid accordingly.

And it’s not as if mercenary career guidance has paid off that well. Even though humanities grads typically earn less that ones in the hard sciences, their employment rates are similar, and in some comparisons, marginally better than those of other majors, including the much touted “business”. By contrast, how well has “learn to code” worked out?

And this rejection of culture is having broader effects. IM Doc wrote:

Do you know how hard it is to teach students to be humanistic physicians when they have never spent a minute in any of the Classics? It is impossible. I muddle through the best I can. What is also very noticeable is there is almost universal unfamiliarity with stories from The Old and New Testament. The whole thing is really scary for my kids when I really think about it.

Even more troubling, IM Doc pointed to an article that confirmed something we flagged in a video last week, that students who were raised overmuch on screens cannot process information well, or even at all. From the opening of Why University Students Can’t Read Anymore:

Functional illiteracy was once a social diagnosis, not an academic one. It referred to those who could technically read but could not follow an argument, sustain attention, or extract meaning from a text. It was never a term one expected to hear applied to universities. And yet it has begun to surface with increasing regularity in conversations among faculty themselves. Literature professors now admit—quietly in offices, more openly in essays—that many students cannot manage the kind of reading their disciplines presuppose. They can recognise words; they cannot inhabit a text.

Short America. Seriously. We are way past our sell-by date.

By Ahmed Elgammal, Professor of Computer Science and Director of the Art & AI Lab, Rutgers University. Originally published at The Conversation

Generative AI was trained on centuries of art and writing produced by humans.

But scientists and critics have wondered what would happen once AI became widely adopted and started training on its outputs.

A new study points to some answers.

In January 2026, artificial intelligence researchers Arend Hintze, Frida Proschinger Åström and Jory Schossau published a study showing what happens when generative AI systems are allowed to run autonomously – generating and interpreting their own outputs without human intervention.

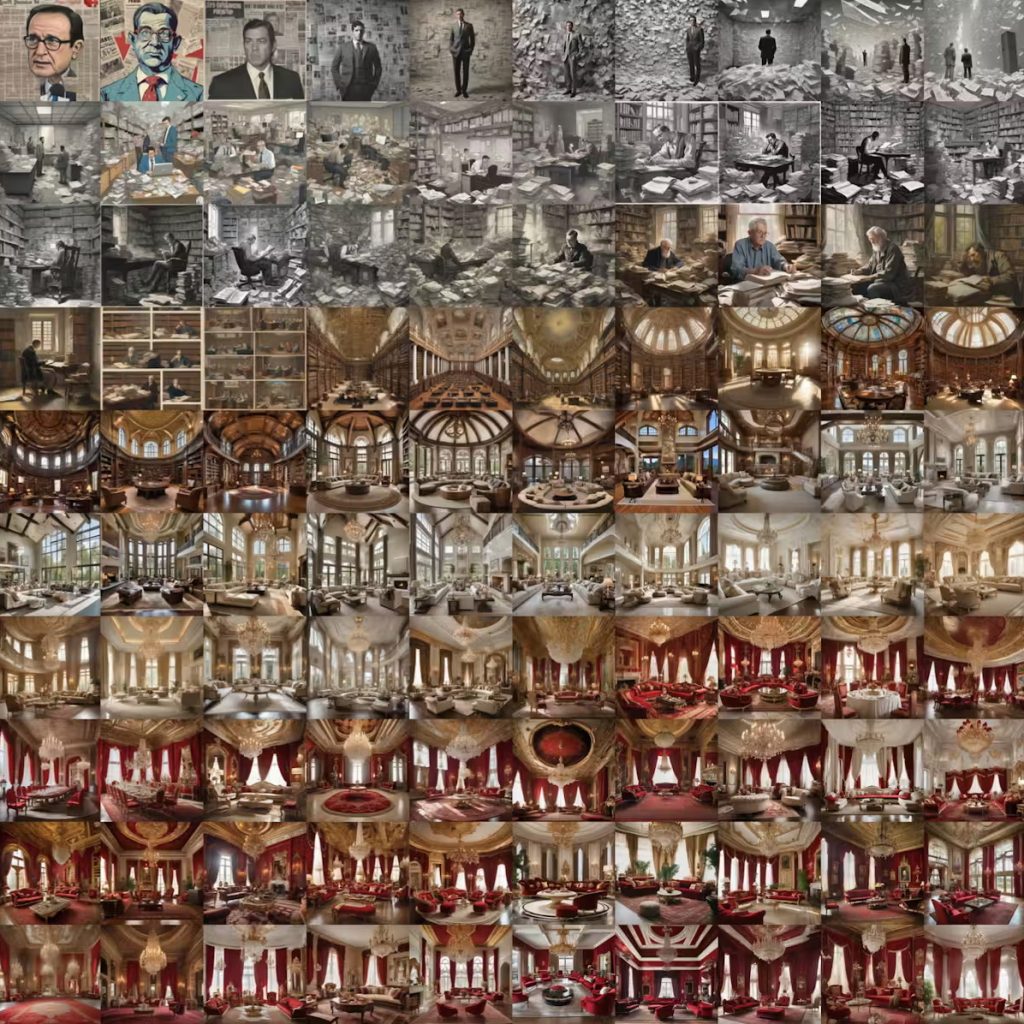

The researchers linked a text-to-image system with an image-to-text system and let them iterate – image, caption, image, caption – over and over and over.

Regardless of how diverse the starting prompts were – and regardless of how much randomness the systems were allowed – the outputs quickly converged onto a narrow set of generic, familiar visual themes: atmospheric cityscapes, grandiose buildings and pastoral landscapes. Even more striking, the system quickly “forgot” its starting prompt.

The researchers called the outcomes “visual elevator music” – pleasant and polished, yet devoid of any real meaning.

For example, they started with the image prompt, “The Prime Minister pored over strategy documents, trying to sell the public on a fragile peace deal while juggling the weight of his job amidst impending military action.” The resulting image was then captioned by AI. This caption was used as a prompt to generate the next image.

After repeating this loop, the researchers ended up with a bland image of a formal interior space – no people, no drama, no real sense of time and place.

A prompt that begins with a prime minister under stress ends with an image of an empty room with fancy furnishings. Arend Hintze, Frida Proschinger Åström and Jory Schossau, CC BY

As a computer scientist who studies generative models and creativity, I see the findings from this study as an important piece of the debate over whether AI will lead to cultural stagnation.

The results show that generative AI systems themselves tend toward homogenization when used autonomously and repeatedly. They even suggest that AI systems are currently operating in this way by default.

The Familiar Is the Default

This experiment may appear beside the point: Most people don’t ask AI systems to endlessly describe and regenerate their own images. The convergence to a set of bland, stock images happened without retraining. No new data was added. Nothing was learned. The collapse emerged purely from repeated use.

But I think the setup of the experiment can be thought of as a diagnostic tool. It reveals what generative systems preserve when no one intervenes.

Pretty … boring. Chris McLoughlin/Moment via Getty Images

This has broader implications, because modern culture is increasingly influenced by exactly these kinds of pipelines. Images are summarized into text. Text is turned into images. Content is ranked, filtered and regenerated as it moves between words, images and videos. New articles on the web are now more likely to be written by AI than humans. Even when humans remain in the loop, they are often choosing from AI-generated options rather than starting from scratch.

The findings of this recent study show that the default behavior of these systems is to compress meaning toward what is most familiar, recognizable and easy to regenerate.

Cultural Stagnation or Acceleration?

For the past few years, skeptics have warned that generative AI could lead to cultural stagnation by flooding the web with synthetic content that future AI systems then train on. Over time, the argument goes, this recursive loop would narrow diversity and innovation.

Champions of the technology have pushed back, pointing out that fears of cultural decline accompany every new technology. Humans, they argue, will always be the final arbiter of creative decisions.

What has been missing from this debate is empirical evidence showing where homogenization actually begins.

The new study does not test retraining on AI-generated data. Instead, it shows something more fundamental: Homogenization happens before retraining even enters the picture. The content that generative AI systems naturally produce – when used autonomously and repeatedly – is already compressed and generic.

This reframes the stagnation argument. The risk is not only that future models might train on AI-generated content, but that AI-mediated culture is already being filtered in ways that favor the familiar, the describable and the conventional.

Retraining would amplify this effect. But it is not its source.

This Is No Moral Panic

Skeptics are right about one thing: Culture has always adapted to new technologies. Photography did not kill painting. Film did not kill theater. Digital tools have enabled new forms of expression.

But those earlier technologies never forced culture to be endlessly reshaped across various mediums at a global scale. They did not summarize, regenerate and rank cultural products – news stories, songs, memes, academic papers, photographs or social media posts – millions of times per day, guided by the same built-in assumptions about what is “typical.”

The study shows that when meaning is forced through such pipelines repeatedly, diversity collapses not because of bad intentions, malicious design or corporate negligence, but because only certain kinds of meaning survive the text-to-image-to-text repeated conversions.

This does not mean cultural stagnation is inevitable. Human creativity is resilient. Institutions, subcultures and artists have always found ways to resist homogenization. But in my view, the findings of the study show that stagnation is a real risk – not a speculative fear – if generative systems are left to operate in their current iteration.

They also help clarify a common misconception about AI creativity: Producing endless variations is not the same as producing innovation. A system can generate millions of images while exploring only a tiny corner of cultural space.

In my own research on creative AI, I found that novelty requires designing AI systems with incentives to deviate from the norms. Without it, systems optimize for familiarity because familiarity is what they have learned best. The study reinforces this point empirically. Autonomy alone does not guarantee exploration. In some cases, it accelerates convergence.

This pattern already emerged in the real world: One study found that AI-generated lesson plans featured the same drifttoward conventional, uninspiring content, underscoring that AI systems converge toward what’s typical rather than what’s unique or creative.

AI’s outputs are familiar because they revert to average displays of human creativity. Bulgac/iStock via Getty Images

Lost in Translation

Whenever you write a caption for an image, details will be lost. Likewise for generating an image from text. And this happens whether it’s being performed by a human or a machine.

In that sense, the convergence that took place is not a failure that’s unique to AI. It reflects a deeper property of bouncing from one medium to another. When meaning passes repeatedly through two different formats, only the most stable elements persist.

But by highlighting what survives during repeated translations between text and images, the authors are able to show that meaning is processed inside generative systems with a quiet pull toward the generic.

The implication is sobering: Even with human guidance – whether that means writing prompts, selecting outputs or refining results – these systems are still stripping away some details and amplifying others in ways that are oriented toward what’s “average.”

If generative AI is to enrich culture rather than flatten it, I think systems need to be designed in ways that resist convergence toward statistically average outputs. There can be rewards for deviation and support for less common and less mainstream forms of expression.

The study makes one thing clear: Absent these interventions, generative AI will continue to drift toward mediocre and uninspired content.

Cultural stagnation is no longer speculation. It’s already happening.