It has gotten through to Trump that the state of the economy, and particularly consumer suffering from persistently high costs, aka the affordability crisis, can’t be solved by his barker’s patter about how great things are. So he’s roused himself to try to find some quick and easy wins so he can present himself as Doing Something. One of them is a proposed one-year cap on credit card interest rates at 10%, which would start January 20, conveniently timed to be in place for the midterms and fall away shortly after that.

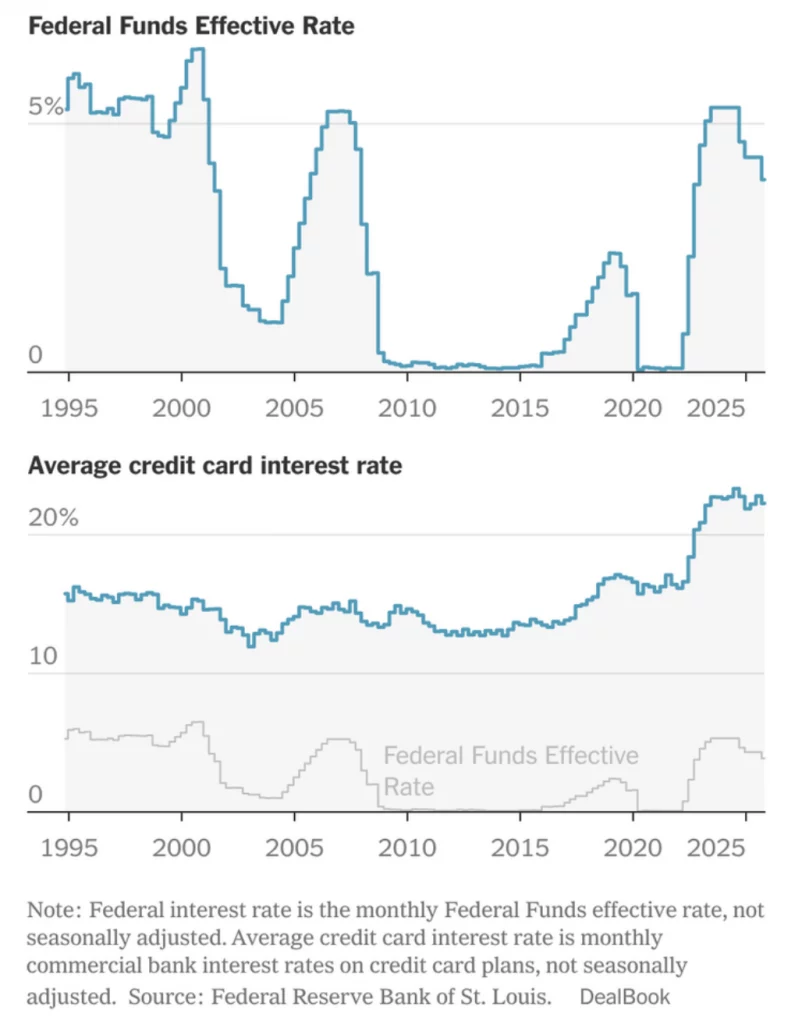

Now with spreads over funding costs having risen so much in recent years, one might think that Trump’s new found anti-bank impulses are well warranted:

US interest rates on credit cards. pic.twitter.com/0NwMqwMFc1

— Steve Hall (@ProfHall1955) January 11, 2026

Another cut of the data, courtesy Andrew Ross Sorkin of the New York Times’ Dealbook:

Except like the arsonist who shows up at a blaze with the firefighters, Trump did help create that problem:

Trump promised to cap credit card interest rates at 10% and stop Wall Street from getting away with murder.

Instead, he deregulated big banks charging up to 30% interest on credit cards.

The result? Last year, JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon made $770 million.

Unacceptable.

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) January 9, 2026

But Trump is just watering down another bad if appealing-sounding proposal, a five-year 10% rate cap put forward by Bernie Sanders, Josh Hawley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Anna Paulina Luna last year.

We hate to be the realist bearing unwelcome tidings, but as is so often the case, easy-sounding fixes to messy problems are seldom what they are cracked up to be. Here, sadly, it is both true that banks are making out overmuch like bandits on credit card charges, yet the simple-minded expedient of a 10% one-year cap will on the whole make matters worse, particularly for those in the most perilous financial shape. Our running buddy back in the foreclosure crisis days, Adam Levitin of Georgetown Law, who is a fierce critic of banks and credit card practices, minces no words. From a post on his Credit Slips blog:

The 10% rate cap was a terrible idea in 2025 and it’s a terrible idea now. It really doesn’t matter which end of the horseshoe it comes from. While it might sound great to get cheap credit, there’s no free lunch here…

I also have no issue conceptually with usury laws…But there’s a smart way to do them and a dumb way, and this is just plain dumb. The rate cap is inflexible and drastically too low. Simply put, the function of a rate cap on credit should be to protect against truly unmanageable credit at the margin. The policy reasoning behind usury laws is a suspicion that anyone borrowing at an extremely high rate is either uninformed or under such financial distress that they cannot say no. In other words, usury laws are meant to address concerns about market failures. It is not an affordability tool for the broad middle class. You cannot fix the economic strains on the middle class through credit policy, and you might even make them worse. To paraphrase a former blogger on this site, credit is a bandaid, not a life raft.

As many as 80% of customers would be money-losers under current credit terms, per Itamar Drechsler, a finance professor at Wharton.

This video on the Wharton findings, posted before the Trump proposal went live, explains why. With an astonishing average pool rate of over 23% (the Consumer Finance Credit Bureau found that as of December, the average rate was 25.2%), banks spend a lot of money on marketing to find and acquire new victims, um, customers. Rewards like cashbacks or airline miles are another big expense:

It is true that banks are making an awful lot of money on credit card interest charges.1 The evidence is not just the amount lead-opponent-to-interest-rate-cap JP Morgan is making, per Bloomberg:

Credit cards are major business for JPMorgan. Such loans totaled $247.8 billion at the end of December. In total, the bank’s card-services and auto business generated about $7.28 billion in revenue during the fourth quarter.

Mind you, this is not apples to apples since the revenue figure is for two businesses and includes a whole lotta other credit card revenue items, like annual fees, late fees, and critically, very juicy merchant discounts. But it is attention-getting.

But an indicator of how good the “charging interest” part of the business is that JP Morgan and other banks are keeping the loans on their balance sheets. A crude generalization is that banks retain loans (as opposed to securitize them) when there’s enough profit to compensate for their equity costs.

But the reason this can’t be harvested in a brute force manner by the proposed cap is that the issuers have engaged in a competitive arms race. In seeking more incremental revenue, they’ve added to costs and overheads. So they do make a lot of money, but as Levitin contends, the volumes are enormous, but the margins, not so much.

But regardless, this is simply na ga happen. First, the Trump scheme would require legislation, which both means that lobbyists could get their teeth into a draft bill plus the timing would impede consumers getting much if any relief by midterms. And many nerdy issues would need to be sorted out.2

Second, as we suspected and Levitin confirms, taking all that income from banks is a Fifth Amendment taking, and under very well established eminent domain rulings, they’d need to be compensated for the loss. Levitin takes a stab at how much consumers might save, which is a point of departure for how much banks might sacrifice:

Nationally, there’s about $1.23 trillion in card debt. But not all of that is part of revolving balances. 43% of cardholders paid their account balances in full each month in 2024, but that accounts for only 18% of outstanding dollar balances. So we need to reduce the relevant total debt outstanding to about $1 trillion. Additionally, the average rate on new offers is around 24%, but a sizable portion of outstanding ($352 billion) is at zero percent promotional rates and wouldn’t be affected by a rate cap. Instead, only about $657 billion would be affected.

If the average rate on those balances is 24%, continuously compounded, then a reduction to 10% would over the year save consumers around $109 billion.

Individually, the average card balance is (a bit under) $7,000 and the average rate is 24%, compounded continuously. Reducing that to 10% generates annual savings of about $1,162.54.

These “savings,” however, are just the reduction in interest paid on cards (assuming no change in balances). They do not account for the knock-on effects of capping card rates, which are likely to eat away much, if not all of the savings.

So even if in an alternative universe, a bill would pass and be signed into law, the banks would smartly march into court to have it declared unconstitutional. The whole matter would be in litigation easily until Trump had left office. No midterm bennies for him!

The users set to suffer most are those who are heavy users but not yet maxed out. Recall that even a consumer carrying a balance will not be charged interest until the charge has not been paid, as in actually gone on the statement and then that statement’s due date has passed. The Credit Card Act of 2009 allows banks to apply only the minimum payment to the lowest interest balances first; they are then required to credit the rest to the highest interest balances.3 Keep in mind we have been discussing only purchases; banks also charge interest on balance transfers, which regularly offer a teaser rate of a few months to perhaps as long as 18 months,4 and then a nosebleed interest rate kicks in. Devising, targeting, and hawking those balance transfers is no doubt a big part of the marketing costs we mentioned earlier.

Moreover, renting a car pretty much requires a credit card, so having them cancelled or credit lines cut to the existing balance would be very difficult for some. A few? A few more than a few? Even if the number is not that large, the consequences for this cohort alone would be serious. Levitin unpacks some of the consequences:

As a starting point, it’s important to recognize that it is impossible to operate a general card program profitably at 10% interest unless it is very heavy on transactors with high credit scores. Card issuers depend on three sources of revenue: interest, fees, and interchange and have cost of funds, credit losses, operating expenses, and rewards costs. If interest is 1000 bp, fees 250bp and interchange 800 bp, with cost of funds at Federal Funds (currently 364bp) credit losses (lets say 500bp on a blended portfolio), 500bp in operating expenses and 700bp in rewards, we are already in negative territory (-14bp). To even start to attract investment, the issuer would have to net at least 300bp, I’d think.

On a subprime portfolio it would be worse, with credit losses at 800bp (interchange and rewards would both be lower, say 400bp and 300bp respectively, but would net out around the same). So we’re talking about issuers operating at a loss of about 300bp, putting us at least 600bp in the hole. It’s hard to see a way that this will work at 10% interest without changing other parts of the card issuer business model.

If card issuers can’t operate profitably at 10%, what will they do? … the most likely outcome will be a huge contraction of credit card lines, particularly for borrowers with lower credit scores.

The effects will be devastating. Families that need the short-term float or the ability to pay back purchases over several months, won’t have it. How will they pay for a new water heater when the old one goes out and they don’t have $3,000 sitting around? …

The contraction of card credit will also be a pain in the butt for families that rely on credit cards for convenience liquidity—they’ll have to find another way to pay for all the streaming subscriptions and Amazon–and their rewards points will get squeezed. Chances are that we’ll see more use of debit cards with overdraft lines. That’s a bad trade given that legal protections for debit card users are weaker than for credit card users and overdraft lines can be much more expensive than a credit card if one is a “sloppy payor.”

A non-exclusive alternative to a contraction in credit availability would be an increase in credit card prices other than interest. I doubt we’d see much revival of annual fees, but the back-end, behaviorally contingent fees and junk fees (“network security fee” sort of thing) one finds are likely to proliferate.

But the fee increase I’d really expect to see would be merchant fees. Merchants really have no ability to bargain over these things (a couple of really big merchants aside), so that’s the easiest place for card issuers to seek to recover revenue. And increased merchant fees will mean higher prices at the register (or less customer service from merchants). There really is no free lunch…..

So whom does a 10% rate cap help? It helps politicians who want to make a show of helping on affordability, but don’t really care about the consequences. And maybe, just maybe, it helps some small set of people whose cards aren’t cancelled with some subsidized credit. But for most people, it will result in disruption to their personal finances, a loss of credit access, and a need to turn to other, less reputable and less convenient sources of credit. It’s a loser of an idea, whether it comes from Bernie or Donald. The idea of a 10% rate cap has all the seriousness of bread-and-circuses governance.

And what about those who otherwise depended on their credit cards for what can be unduly politely described as cash flow management? They might try friends and family first, but a lot will wind up at payday lenders, loan sharks, or the new trap of “buy now, pay later” loans. Buy now, pay later loans were the reason we heard of Charlie Kirk. A friend pointed out that they had become such a plague on campuses that Kirk was hearing of about debt-trapped students and described his alarm and disapproval in a Tucker Carlson interview.

If you think credit cards are evil, that should go double for buy now, pay later loans. They focus on subprime borrowers. They don’t charge interest but instead late fees that are a very rich interest rate equivalent. The lack of interest also helps them escape regulation as a lender. And the really nasty part is they make sure they get paid first. Users have to agree to let the buy now, pay later moneybags reach directly into their bank account on the due date (which the borrower can reset but only by incurring fees….).

The mainstream media is voicing similar concerns, albeit with much less detail and authority than Levitin, such as USA Today’sTrump’s 10 percent cap on credit cards may hurt more than some imagine. The Los Angeles Times’ Mike Hiltzik has a well-detailed and argued take in Trump is demanding a 10% cap on credit card interest. Here’s why that’s a lousy idea. A representative section:

A hard cap on interest rates “could create a sharp contraction in the kind of credit available in the marketplace,” says Delicia Hand of Consumer Reports. “It sounds good, but there could be unintended consequences, especially if you don’t think about what fills the gap,”

Alternative products aren’t regulated as stringently as credit cards. “Direct-to-consumer products can layer subscription fees, expedited access fees, and ‘voluntary’ tips in combinations that produce effective annual percentage rates ranging from under 100% to well over 300% — and in some documented cases, exceeding 1,000% when annualized for frequent users,” Hand said in remarks prepared for delivery Tuesday to the House Committee on Financial Services.

I am old enough to remember when credit cards were not pernicious. Once upon a time, credit card issuers universally charged annual fees. That meant they made money on all customers: ones who used cards rarely, ones who paid their charges in full every month, ones who ran up balances due to Christmas spending and paid that off early in the next year, and those who borrowed all the time. Accordingly, banks were pretty stringent about issuing credit.

When I was at McKinsey, sometime between 1985 and 1987, a Lazard investment banker called me to sanity check a position he was taking in the offering memorandum for a financial services company. He planned to take a strong-form position that the model described above was super attractive and the incumbents knew it and would not change it.

I told him he could not assume that. Just because there were no prospects or rumors I was aware of about industry members planning big shifts did not mean it could never happen.

It was only a few years later that banks started introducing no-fee cards and their business model changed to having lending be the big source of profit on the consumer side. And that evolved to seeking or creating chronically indebted users.

Credit cards do need to be reined in, but not in a lazy, headline-grabbing, casualty-inducing manner, but to get banks out of the business of creating chronic debtors for fun and profit. And that also means cracking down on payday lenders and buy now, pay later operators. But Trump and his team lack the attention span for anything that is either hard or genuinely salutary for ordinary Americans.

_____

1 For simplicity sake, we will not address American Express, since they run an integrated system and handle both customers and merchants (which they call “service establishments”) under the same roof. In the Visa-Mastercard world, a bank will handle its own retail and business card members, which includes deciding which ones get credit lines, what fees and interest rates they charge, and how they handle late payments, delinquencies, and defaults. On the “merchant” side, they may charge minimum monthly fees or set minimum transaction volumes for fee-free status, and apply “merchant discounts” (how much of the customer charge they retain) or other transaction-based fees. They also adjudicate customer disputes with merchants, aka chargebacks.

2 From Levitin:

My understanding of the President’s proposal is that he wants a temporary 1-year cap on credit card interest rates at 10%. What exactly does that mean? I’m not sure.

- Is that 10% interest rate or 10% APR? Those aren’t the same thing. If the former, is it simple interest or compounded (and how frequently)? If the latter, it is going to really hit cards with annual fees.

- Does 10% apply to all balances (as under Sanders-Hawley) or just purchase balances? If it’s everything, it’s basically creating low-cost leverage for cryptocurrency speculation and sports gambling (usually treated as cash advances, which have a higher interest rate than purchase balances).

- Does 10% override penalty rates for delinquent accounts?

- What happens at the end of the year? Would rates spring back to their contractual levels only on future balances or also on existing balances? And if they spring back, would it be applied to balances going back into the 1-year or only prospectively? These mechanics matter.

On some level these are all in-the-weeds details, but the point is that rate caps aren’t so simple, especially with revolving balances. Making laws work well requires getting the plumbing and wiring right. That sort of technical stuff is weedy, but really, really matters.

3 From NerdWallet:

The amount you owe on your credit card may appear on your statement as one number, but when it comes to how credit card payments work, it gets murkier. Depending how you’ve used the card, your total debt might be split into separate balances, such as:

-

A purchase balance, for things you bought with the card.

-

A cash advance balance, for money withdrawn from ATMs with the card.

4 “Life of the balance” offers were A Thing before the crisis. I don’t recall seeing any since then. Perhaps enough users were successful in gaming them and never triggering a penalty rate?