On one of his YouTubes, Gonzalo Lira and I discussed what I called belief clusters, that those who held one set of views were assumed to subscribe to a related set of opinions. A noteworthy example is how nearly all the anti-globalist commentary community (at least as on YouTube and Substack) hew to simple-minded black and white stories about the the brutal and retrograde US led hegemony, desperately trying to hang on to dominance, is opposed by a virtuous Global Majority seeking to establish a fairer new order. Part of this stereotyping is to contrast the US’ colonial and predatory actions towards other countries with China’s supposedly beneficial or at least benign economic posture

Sadly, we think the degree of difference, based on what we have seen here in Thailand and the example of Africa shows, is more like the distinction between Team Republican and Team Democrat in the US. As Lambert put it,

The Republicans tell you they will knife you in the face. The Democrats say they are so much nicer, they only want one kidney.

What they don’t tell you is next year, they are coming for the other kidney.

Admittedly, the US under Trump has become so unabashedly piratical that just about anything else looks good by comparison. But “good by comparison” should not be confused with good. Some commentators are coming to this recognition, as we discussed long form in “BRICS Are the New Defenders of Free Trade, the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank” and Support Genocide by Continuing to Trade with Israel.

Today, we will rely heavily on an in-depth story from Patrick Bond, professor at the University of Johannesburg Department of Sociology, in Africa deindustrialises due to China’s overproduction and Trump’s tariffs. Note that this is posted at the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt site, which is firmly anti-neoliberal and anti-colonial, as well as Marxist leaning.

Bond’s discussion of China relies on in-depth analyses and local readings, such as the book The Material Geographies of the Belt and Road Initiative, edited by Elia Apostolopoulou, Han Cheng, Jonathan Silver and Alan Wiig , world-systems sociologist Ho-fung Hung, and Irvin Jim of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA.)

We are quoting Bond liberally in part because his argument is chock full of supporting information, and also because he regularly and explicitly counters the views of Vijay Prasad, with Bond carefully explaining why he depicts Prasad as a China optimist.

I am sympathetic with Bond’s position based on what I have seen in my comparatively short time in Southeast Asia. The English language press goes to some lengths to be inoffensive, which means hewing to well-accepted view. It has sometimes taken up complaints I have heard from locals of predatory Chinese business practices, such as zero dollar exports and zero-dollar factories. There was additional unhappiness after the Liberation Day tariffs kicked in, with China diverting shipments to Southeast Asia, not just in an apparent attempt to evade the US tariffs via trans-shipments (something the Trump Administration sternly warned area governments to prevent, not that they can readily do so) but also as a form of dumping. This is occurring despite considerable family and commercial ties between the Thai elite and important interest in China. One would have to think governments and enterprises in Africa would be less well equipped to handle challenges like these.

We’ll give only a short recap of the Trump-created damage since it is generally better known and hews with the priors not just of anti-globalists but also Trump opponents, and then turn to the less-well understood profile of Chinese exploitation. A reason China’s conduct may be less well understood is that it may be mistakenly analogized to the Africa/developing world practices of the old Soviet Union. The former USSR, unlike China, had little need to secure resources and did not have a profit motive even if they did want to secure other benefits from their support of developing countries. Contemporary China is not in the same position.

Trump’s policies have unquestionably harmed Africa. Trump and his white supremacist sidekick Elon Musk ended most had wiped out most U.S. emergency food, medical and climate-related support for Africa, with South Africa getting the extra kick of extra contract cuts. On the trade front:

Then came Trump’s devastating tariffs – in February, April and again in August – followed by the September demise of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) which since 2000 had given dozens of African countries duty-free access to U.S. markets. Notwithstanding a deeper context of dependency relations associated with AGOA – for as political economist Rick Rowden points out, “gains were largely due to African exports of petroleum and other minerals, not manufactured goods” – these latter trade-curtailing processes were exceptionally damaging, wiping out 87% of auto exports from South Africa in the first half of 2025.

The World Bank concluded of 2025’s tariff chaos, “industry-level impacts may be significant in global value chain–linked activities, notably, textiles and apparel as well as footwear (Eswatini, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, and Mauritius) and automotive and components (South Africa)… Loss of the AGOA would sharply reduce exports to the United States. On average, exports would decline by 39% if a nation were suspended from AGOA benefits.”

Demand from the rest of the West is set to fall, thanks to new European regulations plus weak growth.

A must-read, detailed section of Bond’s article documents the extent and severity of China’s overinvestment/overcapacity problem, depicting it as the most prominent part of a classic Marxist capital overaccumulation. He describes in detail how, starting in the early 2010s, the Belt & Road initiative allowed Chinese companies to remedy their in-country overproduction problem by expanding along its routes.

A representative part on how the global overproduction problem is primarily a Chinese one:

Mostly though, excess capacity is the core signal, as some crucial sectoral examples show:

-

global steel output of nearly 1.9 billion tonnes in 2024 contrasted to 2.47 billion tonnes of capacity (i.e., 76% capacity utilisation), with a rise of another 10% excess capacity estimated in 2025, to 680 megatonnes;

-

in chemicals, Bloomberg News reported earlier this month, “A wave of new Chinese petrochemical plants is raising fears of a deluge of exports that will put pressure on other producing nations that are already struggling with oversupply” due to “seven massive petrochemical hubs… creating a global glut that could swell even further if more planned plants come online” at a time, in 2025, polyethylene output rose 18%;

-

China’s annual vehicle production capacity – carrying either internal combustion engine or electric motors – was 55.5 million vehicles/year capacity in 2024, but was only half utilised (just 27.5 million vehicles were produced that year), while in 2025, Chinese output was expected to reach 35 million (still a low capacity utilisation), displacing other economy’s sales and leaving the world with increased idle capacity, as global vehicle sales languish at 90 million;

-

also in China, “The root cause of the cement sector’s current difficulties lies in the long-standing problem of overcapacity, which has now been amplified by weaker market demand” since 2021 “due to declining property investment and a slowdown in infrastructure construction,” according to the China Building Materials Federation, and

-

solar photovoltaic panels generated nearly 600 GW of new power in 2024 – mostly emanating from China – but there was, at that point, more than 1,000 GW of annual manufacturing capacity, and to store the power, lithium-ion batteries were produced at the scale of 2.5 TWh in 2023, but by 2024 there was 3 TWh of capacity and projections of 9 TWh by 2030, at a time demand was expected to rise only to 5 TWh.

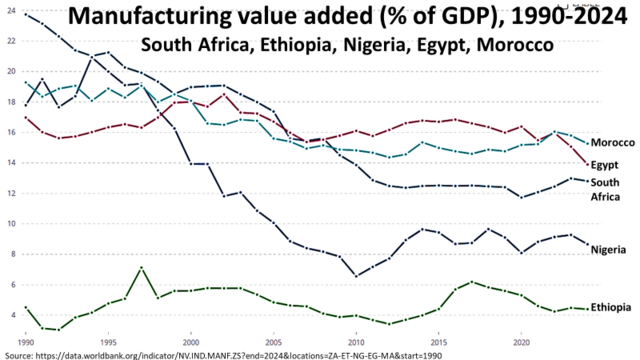

Bond describes how the countries in Africa that were most industrialized have seen the size of their manufacturing sectors fall relative to the size of their economy; even the supposed Chinese success story of Ethiopia saw gains largely eroded. Per Bond:

…there are too many instances of adverse impacts from Chinese capitalism in Africa: deindustrialisation through swamping local markets with surpluses (as NUMSA complains), especially as the displacement of Trump’s tariffs; broken promises on Special Economic Zone investments; brazen but unpunished corruption; excessive lending and then sudden cuts in credit lines; and heinous corporate behavior especially in the extractive industries, including extreme ecological damage. Each needs elaboration, in the pages below.

And one test case deserves more consideration: the rapid deindustrialisation of South Africa underway in recent months thanks to the ‘dumping’ (i.e. sale at below the cost of production) of Chinese overaccumulated capital, according not only to the government in Pretoria – which in recent months punished imported Chinese steel, tyres, washing machines, and nuts and bolts with new tariffs – but also to NUMSA (which wants the same for cars), although it is ordinarily very pro-China. In South Africa, the manufacturing/GDP ratio was 24% in 1990 and has now sunk to 13%.

Formidable Chinese product competition means the African economies mentioned by Prashad as the continent’s lead industrial production sites, plus the largest in population (Nigeria), have not improved their manufacturing/GDP ratios since that 2015 FOCAC industrialisation hype. Most such ratios, like South Africa’s, had already collapsed in the first round of 1990s-era trade liberalisation.

The optimal test case that many pointed to during the mid-2010s as Africa’s cutting-edge industrialisation site, was Ethiopia, thanks to the sudden emergence of (largely sweatshop) manufacturers mainly in Addis Ababa, whose products benefited from the new train line to the port of Djibouti, built with the assistance of Beijing. As a result of the influx of Chinese firms’ local production of clothing, textiles, footwear and other light-industrial output, Ethiopia’s manufacturing/GDP rose rapidly from 3.4% at the low point in 2012, to 6.2% in 2017.

However, that ratio subsequently fell to 4.3% in the period 2021-24. As the International Monetary Fundexplained, “The share of manufactured goods such as textiles, leather and meat product in total exports had grown to 13.5% in Fiscal Year 2018/19, from a small base, but declined sharply thereafter to around 4% in the first nine months of FY2024/25, due to the pandemic, conflict, suspension from AGOA, and foreign exchange shortages that limited availability of intermediate imports.”

Those hard currency shortages led to a major financial crisis in late 2023…As a result of the default, Ethiopia was initially not permitted to become a formal member of the BRICS New Development Bank, for potential hard-currency credit infusions (nearly 80% of that bank’s lending is in the dollar or euro), although it is scheduled to join, at some stage….

Will Beijing step in? In aggregate, Chinese aid, investment and loans to Africa have also fallen since mid-2010s peaks, which also affected states’ foreign exchange reserves. China’s own new public and publicly-guaranteed loans to Africa collapsed from $32 billion in the peak year of 2016, to $1 billion in 2022. The year-end 2025 African foreign debt of $1.3 trillion includes $182 billion in Beijing’s known public and publicly-guaranteed loans.

Bond also takes issue with the widely-accepted view that China is generous in its debt restructurings when Belt & Road borrowers have trouble meeting obligations. This is again the fallacy of seeing something that is less bad than IMF “rescues” as good. Bond describes how poorer countries like those in Africa are treated more harshly than middle-income debtors:

China’s own new public and publicly-guaranteed loans to Africa collapsed from $32 billion in the peak year of 2016, to $1 billion in 2022. The year-end 2025 African foreign debt of $1.3 trillion includes $182 billion in Beijing’s known public and publicly-guaranteed loans.

China had taken a decision in 2021, AidData researchers remind, to fund 128 rescue loan operations in 22 low-income countries facing debt distress, costing $240 billion. These included five African states – Angola, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania and Kenya – among which low-income borrowers were “typically offered a debt restructuring that involves a grace period or final repayment date extension but no new money, while middle-income countries tend to receive new money – via balance of payments (BOP) support – to avoid or delay default… These operations include many so-called ‘rollovers,’ in which the same short-term loans are extended again and again to refinance maturing debts.”

The 2024 FOCAC did, however, denominate more financial flows in the Chinese currency, which could facilitate trade, alleviate forex shortages, and also lower transactions costs. Yet devils are in the details, for against all the logic argued above, according to the Centre for Global Development (which is generally neoliberal and welcomes Chinese lending):

Between 2015 and 2021, commercial creditors contributed about a third of all Chinese lending commitments over that period. These commercial lenders overtook policy banks between 2018 and 2021 … [and] are market-oriented, with loans that are more expensive and with shorter maturity than state-owned counterparts. Their need for risk mitigation, usually through Sinosure, raises the financing costs even higher. Over the next five years, a continuation of this trend where Chinese commercial lenders become an ever-larger segment of lending to Africa at non-concessional rates will only heightens the risks of debt distress.

Bond even dares raise the third rail issue (in left-leaning/anti-globalist circles) of whether China, in its quest to secure resources, is looting Africa. That’s a reasonable question given the increasing role China has played in the continent even, as we showed above, manufacturing value added has fallen in the most industrialized countries. Bond addresses the argument by China-defenders like Vijay Prasad, that Chinese firms have been competing in Africa with Global North concerns, with the result that competition has resulted in African nations getting better terms and, arguably, China is being unfairly charged with using African resources to build products often destined for first world markets. Bond makes a variant of our “coming for your kidneys over two years does look less bad than being knifed in the face” argument. From the article:

As noted above, there are usually three categories to consider, of ecological reparations due to non-renewable resource depletion, greenhouse gas emissions and other forms of localised pollution….

Indeed this subimperial location within global value chains makes China subject to an unequal ecological exchange critique. For behind the general need for resource extraction and (limited) processing of minerals that goes on in Africa, are scandalous conditions. Without sinking into Sinophobia, it is useful to recall some of the highest-profile cases, because Beijing simply fails to respond to the obvious need to curtail Belt and Road abuse by Chinese firms:

- in the DRC in November, Congo Dongfang International Mining leaked toxic pollution into the Lubumbashi River near the country’s second largest city, while nearby at Kalando, informal miners (75% of whom across the DRC sell their wares to Chinese buyers) suffered at least 50 deaths in a mountainside collapse that compelled the government to ban artisanal copper and cobalt mineral processing, in the wake of non-payment of billions of dollars’ worth of royalties to the government by Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, Ningxia Orient, JiuJiang JinXin and Jiujiang Tanbre smelters – all within Apple’s supply chain – which in turn resulted in a major lawsuit by the Kinshasa regime and by a U.S. public interest agencyagainst the California corporation, and similar non-payment accusations were made by Kinshasa officials against China Molybdenum’s super-exploitative Tenke Fungurume cobalt mine;

- in Zambia’s copperbelt in February, negligence by Sino-Metals Leach and NFC Africa Mining caused a slime-dam break – of 1.5 million tonnes of cyanide- and arsenic-laced sludge – into the Kafue River, resulting in an $80 billion lawsuit by some of the 700,000 affected residents adjacent to Zambia’s main internal waterway and second-largest urban region;

- in the Central African Republic’s mines, there was slave-like human trafficking of Nigerians – who went unpaid for a year in 2024-25 – by Rado Central Coal Mining Company;

- in Ghana, Shaanxi Mining extracted gold in a manner that amplified the ‘galamsey’ artisanal mining crisis;

- in Zimbabwe, there are countless complaints against Chinese mines, for looting $13 billion of Marange diamonds by the military-owned parastatal Anjin (as even President Robert Mugabe alleged in 2016), for the murder of a dozen Mutare artisanal gold miners in 2020 by Zhondin Investments, for mass displacement and pollution at the Hwange coal mine by BeifaInvestments, for illegal mining in national parks by Afrochine Energy and Zimbabwe Zhongxin Coal Mining Group, and for Sinomine Resource Group’s failure to respect beneficiation requirements at the continent’s largest lithium mine, in Bikita, in addition to other Chinese lithium miners at Kamaviti, where as a result, Centre for Natural Resource Governance director Farai Maguwu alleged in late December, “Zim is the biggest donor to China, and not the other way round”;

- in South Africa, the corruption of rail parastatal Transnet by Chinese locomotive suppliers empowered the notorious Gupta ‘state capture’ family, while at two chaotic Special Economic Zones, Chinese investors included an Interpol red-listed looter of a Zimbabwean mine and two auto producers (FAW and BAIC) whose job creation and production promises were not kept; and

- in the two main oil and gas controversies in Africa, state-owned China National Overseas Oil Corporation is building a heated pipeline (the world’s longest) from western Uganda to Tanzania’s port of Dar es Salaam, and state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation’s participation (with partners ExxonMobil and ENI) invested in a long-delayed northern Mozambican ‘blood methane‘ gas extraction project, in the midst of a civil war with Islamic guerrillas that since 2017 has displaced one million people and killed many thousand – and in both cases, the ultra-corrupt TotalEnergies leads the projects.

In addition to often-extreme human rights violations, these represent obvious forms of unequal ecological exchange, in which African economies lose net wealth, even if Chinese purchases of raw materials raise levels of foreign exchange and national income, creating (low-paid) jobs and providing a modicum of royalties, taxes and infrastructure.

Typically outweighing such benefits, though, damage is not limited to local pollution and displacement, or to permanent depletion of non-renewable resources that leave both current and future generations impoverished…

On top of this damage, the extraction and processing of minerals also entail an enormous ‘social cost of carbon’ caused by CO2 and methane emissions in mines and smelters…

The latter damage will create new ‘polluter-pays’ climate debtors out of low-income African economies, if the International Court of Justice’s July 2025 advisory opinion on liabilities for socio-ecological reparations is to be taken seriously…

In sum, unless the Chinese state suddenly begins regulating its firms’ emissions and abuse of African resources and people, and finds creative ways to pay a wide range of ecological reparations, it appears extremely unlikely that a genuine industrialisation initiative will emanate from Chinese investors.

So those who want to see China as an enlightened economic power might consider recalibrating their views. One economist noted for his close connections to China has even conceded to me privately when I told him “Now that I am in Thailand, I have a vastly less rosy view of Chinese investment:”

That’s why Chinese businessmen were so widely abhorred throughout Asia. And Chinese officials even bragged to me about how cutthroat they were in their business dealings.

Bsck in the days when Wall Street was criminal at the margin, Goldman described its modus operandi as “long-term greedy”. That is probably the best gloss to put on China’s mercantilism. And don’t kid yourself. Long-term greedy is still greedy.